shocking prohibition-era crimes of sin city

“The time has come to find out who’s running this town – the bootleggers or the officers.”

With the passage of the 18th Amendment and the federal Volstead Act, liquor was by and large made illegal across the United States starting in 1920. This immediately created a lucrative black market for the illicit sale of alcohol, and along with it came an explosion of violent crime as competing rackets fought for control of the new underground market. During Prohibition, the tiny town of Las Vegas was the scene of both homegrown bootleggers and organized crime elements that predated the more familiar Vegas mafia figures by decades.

Las Vegas resident and bootlegger Joe Santini was gunned down outside his home as part of an ongoing feud between rival bootleggers. The local press lamented the “troublesome gangster element” that had taken hold in the city. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

The Troublesome Gangster Element

On the night of April 22, 1932, long-time Las Vegas resident Joe Santini exited the poolhall he owned downtown on Stewart Avenue and made the short walk across the alley that sat between his establishment and his house. Santini opened the gate to the fence surrounding his home and entered his yard. Santini had just finished closing the gate behind him when a flashlight flicked on, shining blinding light into Santini’s face. Two shadowy figures approached and one asked, “Are you the proprietor of this place?”

“Yes,” Santini replied.

Having gotten their answer, one of his assailants fired a single shot that struck the poolhall owner in his abdomen. The shooter let the pistol drop to the ground, then the attackers fled in opposite directions and into the darkness. Meanwhile, Santini stumbled back to his business and collapsed soon after reentering the building. He was rushed to the hospital where the District Attorney and sheriff attempted to get information about the assailants. Santini died within a few days from his wounds, issuing a final statement in his native Italian but before a translator could be summoned.

Several other Italian immigrants associated with illegal bootlegging operations in the Red Light District of Las Vegas fled the city in the days following the Santini murder. Joe Santini had been involved in illegal liquor sales at his poolhall for years as well as having a hand in the management of several local illicit bootlegging operations. Santini was heavily associated with what the Vegas press called the “troublesome gangster element.” The subsequent police investigation discovered that it was a well-known secret among local underworld characters that Santini had been marked for death as a result of a dispute over the local liquor trade.

Things took a further tragic turn a few weeks later when one of Santini’s close friends from the Nevada town of Caliente traveled to Vegas in order to investigate his friend’s slaying. Vittorio Decimo stayed at the same small house in downtown Vegas where his friend had been gunned down. But on the night of May 29, 1932, Decimo was killed by a single shot to his head while lying in bed inside the Santini home, stopped before his independent inquiry into his friend’s untimely death could even begin.

Rumors circulated that the police were paid off, as the killings of Santini and Decimo were two of only three unsolved homicides up to that point in the twenty-seven year history of Las Vegas. Despite Sheriff Keate conducting what publicly appeared to be a diligent search for suspects, the killings remained unsolved.

Prohibition was repealed via the 21st Amendment the year after the twin killings on Stewart Avenue, largely eliminating the power of the underground bootlegging rackets in Vegas.

Bootlegger John Hall murdered his associate after a dispute over an illegal moonshine purchase gone wrong. Press accounts of the time covered the bizarre twists of the Hall murder case. (California Digital Newspaper Collection, UCR)

missing money and a murder

Las Vegas in 1931 was still a small town of 5,000 people, but that was rapidly changing due to one of the largest construction projects in U.S. history taking place thirty miles south of the city – the building of the Boulder Dam.

One recent arrival to Las Vegas around this time was John Hall, a 52-year-old traveler from North Carolina, who arrived to town with his wife and a plan to ply his new trade as a bootlegger in the waning days of Prohibition. While living at a rented cottage located on the isolated Fox Ranch about seven miles south of Las Vegas, Hall met another newcomer – John C. O’Brien, who had recently arrived to the Vegas area with his wife and teenage stepdaughter.

O’Brien eventually approached Hall with a business proposal – O’Brien knew a man willing to sell him moonshine for $2 per gallon. If Hall would front the money for the wholesale purchase of the moonshine, O’Brien would repay Hall with fifty cents on the dollar. Hall was game and the two men shook on the deal.

On a night in early June of 1931, Hall and O’Brien loaded into a car and drove off to meet O’Brien’s contact, with Hall clutching a coffee can in his lap containing $680 (equivalent to about $10,000 today) as they drove over unpaved dirt roads. The meeting with O’Brien’s contact was a bust, but when Hall awoke the next morning, he was missing the $680 from his coffee can. He immediately awakened O’Brien and accused him of stealing the money. “I know this looks bad, but I didn’t take the money,” O’Brien swore to his new friend and business associate.

Two days later, Hall accompanied O’Brien on a trip into Las Vegas to visit a local establishment where O’Brien sold his bootleg liquor. The men later went out that evening with their wives and indulged in heavy drinking.

After the group returned to the Fox Ranch late that night, Hall and his wife stepped out of the car. Hall walked a few feet, but his emotions, loosened by alcohol, took control. He turned back toward the car and said, “Jack, your folks have been spending my money around here pretty free and I have heard some other things. I want to talk with you about them.”

O’Brien began to roll away in his car. Hall demanded that he stop. When O’Brien kept inching forward, Hall pulled out a revolver and emptied it into the driver’s side of the vehicle. O’Brien was hit in the back with three .38 rounds. He would eventually be taken to a local hospital where he died of his wounds. Meanwhile, Mrs. O’Brien and her daughter abandoned their vehicle and ran into the desert seeking safety.

Panic soon set in for Hall at what he had done. He and his wife fled immediately after the shooting. The Halls eventually managed to catch a lift on the back of a passing truck. Hall, still inebriated and consumed by rage at the theft of his money, boasted to the driver of the truck that he “would hate for the boys back in the Carolinas to know” that he had only hit O’Brien with three of his six shots, particularly in light of Hall’s prowess as a marksman while serving in the military in the Philippines.

Hall and his wife remained on the lam for a month before being taken into custody by a California highway patrolman in Yermo. At trial, Hall maintained he was acting in self-defense, alleging that O’Brien had reached for his own pistol prior to Hall opening fire. But his statements to multiple people after the shooting that O’Brien had gotten what he deserved sunk Hall at trial. He was convicted after a day of jury deliberations and sentenced to death.

Hall was transported to Carson City and was brought to the gas chamber at the Nevada State Prison on November 28, 1932. His case briefly made national headlines when it turned out Hall was actually a formerly successful building contractor pre-Depression from Morganstown, North Carolina that had gone missing a few years prior.

Hall went to the gas chamber with a supremely calm demeanor. The prison doctor registered his pulse at a normal 84 beats per minute. He did not even flinch when the cyanide pellets landed into a crock of water, creating the lethal gas.

John Hall was apparently under the belief that a future feat of medical science would be able to bring him back from the dead. He had requested his attorneys to donate his body to a San Francisco doctor that had recently saved the life of a medical student accidentally injected with cyanide. With the medical student, treatment for the cyanide poisoning had been administered before the patient perished, but Hall was apparently under the mistaken impression that he could be revived from death by cyanide poisoning.

The doctor in San Francisco refused to accept Hall’s body.

A scene from The Northern, one of several establishments around Las Vegas that openly flouted laws against the sale of alcohol during Prohibition. (UNLV Digital Collection)

king of the bootleggers

One of the first major arrests in southern Nevada for violating Prohibition laws (Nevada, like many States, had passed its own ban on alcohol) occurred shortly after the celebrations concluded to usher in the new year of 1920. Lon Groesbeck, a well-known resident of Las Vegas who had run into legal troubles in the prior few years for illegal gambling, was arrested on January 2nd. His crime was delivering nearly two dozen bottles of Old McBrayer brand whiskey to The Northern, one of the saloons that continued to operate in the open around Vegas even after Prohibition went into effect.

Certain public officials and the local newspaper had been clamoring for the arrest of Groesbeck for months, with the local paper dubbing him “King of the Bootleggers.” But Clark County Sheriff Sam Gay refused to take action. And Groesbeck would have continued to do his part in keeping Las Vegas a “wet” city had the local District Attorney, A.J. Stebenne, not gone around the sheriff. The District Attorney obtained an arrest warrant directly from the local District Court judge and then proceeded to round up two deputy sheriffs. The D.A. and the deputies set up a few blocks from The Northern to plan the logistics of their raid.

Unfortunately for him, Sheriff Gay was strolling by as the trio plotted how they would enter the drinking establishment. The District Attorney recruited the sheriff as reluctant backup. The four men walked through the front door of The Northern, past a smattering of patrons, and into the backrooms of the establishment. There they encountered Groesbeck in bed and woke the traveling bootlegger. It did not take long for Groesbeck to realize the purpose for this late-night visit. He referenced a half-empty bottle of whiskey on his nightstand and told the midnight interlopers, “There is all I have…you can use that against me if you want to.” Sheriff Gay likely would have been satisfied with that answer, but the District Attorney continued to search the room until he came across a trunk filled with the illicit hooch shipment.

The District Attorney ordered Groesbeck to be placed under arrest and hauled to the county jail. But the bootlegger protested that he was recovering from a severe cold, and he was permitted to continue resting in his bed in the backroom of The Northern. When Judge Henry Lillis set bail at $500 for the well-known bootlegger, Groesbeck wrote a check for the hefty amount on the spot.

Five days later, Lon Groesbeck appeared with his attorney before Judge Lillis, one of the local officials keen on turning a blind eye to the illegal liquor business. The bootlegger entered a plea of guilty, and the judge proceeded to sentence Groesbeck to pay a $400 fine and three months in jail. But the jail sentence would be suspended provided Groesbeck immediately pay his fine and leave the city limits of Las Vegas. Groesbeck happily tendered the $400 and headed back to his room at The Northern.

District Attorney Stebenne adamantly protested Judge Lillis’s decision to suspend the jail sentence, arguing – correctly – that there was no legal basis for the judge to grant this clemency to violators of the Prohibition law. But Judge Lillis stood by his decision, forcing the District Attorney to scramble to prepare the paperwork necessary to appeal the suspended sentence to the presiding judge in the county, Judge William Orr (who later went on to serve as a federal appellate court judge).

Judge Orr granted an order for Judge Lillis to reverse his decision and have Groesbeck imprisoned in the local jail. Judge Lillis had the order of commitment delivered to a deputy sheriff, but the deputy then delayed for over an hour before taking the ten-minute walk to The Northern to make the arrest. But to nobody’s surprise, Groesbeck had taken advantage of the three-hour lag between Judge Lillis suspending his sentence and the deputy arriving to make the arrest to flee Las Vegas in his car - with its notorious hidden false bottom used to store illicit booze - for friendlier environs.

The local newspaper expressed the fury of a certain upstanding segment of the Las Vegas populace, taking particular offense that the only people penalized up to that time under Prohibition were “a few of the drunks and the casual bootlegger – the little fellow – while the chief offenders pursued their calling in security.”

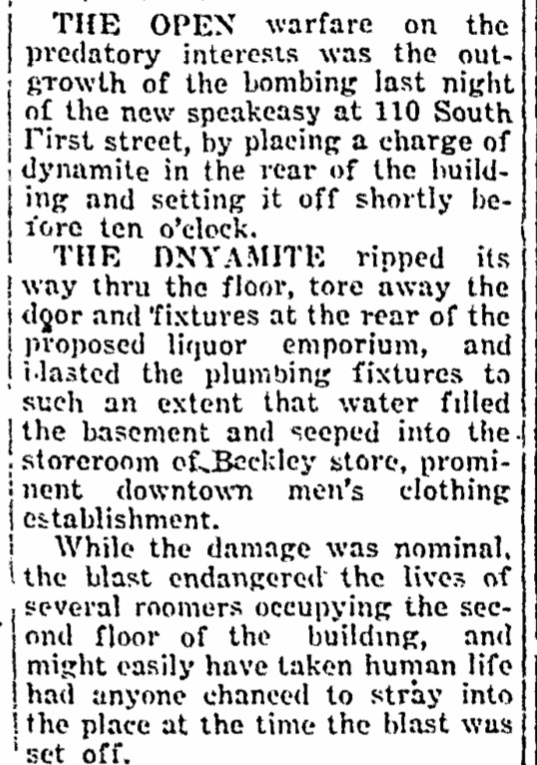

Article recounting the bombing of a downtown Vegas speakeasy in 1932. The local press helped increase pressure for public officials to act against illegal bootleggers. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

a speakeasy bombing

During the night of June 22, 1932 - shortly before 10 o’clock - a bundle of dynamite left at the rear of what was supposed to be the town’s newest speakeasy in the Red Light District of Las Vegas at 110 South First Street blew apart the rear of the building, sending debris flying through the empty bar and shattering the structure’s plumbing fixtures. The basement of the would-be speakeasy flooded, with water seeping into the storage room of a popular men’s clothing store next door. Several boarders were sleeping in rooms above the speakeasy, and though startled, none were injured in the bombing.

The bombed speakeasy was owned by the proprietors of another illegal liquor establishment that operated largely in the open called Number 10 Stewart Street. Well before mobsters from back East made their mark in Las Vegas, the year 1932 saw a gang war erupt between local bootleggers and speakeasy owners across the small town of just a few thousand people.

The owners of Number 10 Stewart Street had been subjected to several armed hold-ups by rival gangs in the months leading up to the bombing. One theory from law enforcement officers at the time was that word had gotten out that the owners of Number 10 Stewart Street had assisted the police in arresting members of the gang responsible for the armed robberies, and the bombing of the speakeasy on First Street was an act of retaliation.

The late-night bombing in downtown Las Vegas created public pressure for an official response, and that response came swiftly. “The time has come to find out who’s running this town – the bootleggers or the officers,” declared Clark County Sheriff Joe Keate the day after the attack on the planned speakeasy. A meeting was convened that same day between Sheriff Keate, Las Vegas Police Chief Clay Williams, and District Attorney Harley Harmon to fight back against the bootleggers.

Local law enforcement promptly shuttered the city’s well-known speakeasies over the next few days, with Sheriff Keate warning of harsh consequences for those that made any effort to reopen the “liquor emporiums” as the local press referred to the establishments. While the speakeasies lining the Red Light District of Las Vegas were shut down, many of the saloons dotting Boulder Highway – the artery connecting Las Vegas to the newly established town of Boulder City – continued their operations without interference in the aftermath of the bombing.

No culprits were ever arrested in relation to the bombing, and with the end of Prohibition in 1933 largely came an end to the violence tied to bootlegging rackets.

Downtown Las Vegas as it appeared at the time of the alcohol-fueled murder of Marcus Wherle by Nick Dugan. (Las Vegas Historical Society)

“Demon Alcohol” on trial

Prohibition came into effect across the nation on January 17, 1920. But Las Vegas in 1920 was an isolated desert outpost, a forgettable stop on the way to and from California, which helped the town manage to largely avoid strong enforcement of Prohibition laws. But the morally crusading local newspaper decried the sight of intoxicated men stumbling about the saloon district and chastised the local authorities for not doing enough to stem the flow of illegal booze.

Tensions over the town’s permissive attitudes toward alcohol came to the fore when on the afternoon of November 22, 1921, a young man by the name of Nick Dugan burst through the door of Lambert’s Café in downtown Las Vegas, walking with an uneasy step. He made his way through the crowded room to the lunch counter where he took his seat in a manner that made his presence known. Dugan hollered over to a waitress, demanding a cup of coffee and a sandwich.

When a waitress brought over the ordered cup of coffee and sandwich, Dugan immediately began yelling obscenities at the woman. One patron in the crowded restaurant had enough of this spectacle. Marcus Wherle, a decade-long resident of Las Vegas, rose from his table and told Dugan, “Shut up and get out!”

Dugan pulled a revolver and turned on Wherle. “You going to make me?” There was a moment of hesitation on the part of Wherle before he made the decision to confront the drunken interloper. Wherle managed to grab Dugan’s wrist and nearly wrestle the gun from his hand, but not before Dugan used his strength to push the barrel of the gun against Wherele’s side and pull the trigger.

A shot rang out in the crowded restaurant. Wherle stumbled back and turned. Dugan fired another shot into the man’s back and Wherle collapsed to the floor. Dugan stepped over his unconscious victim, hurling more obscenities before exiting the establishment by a back door.

When alcohol was involved with a murder, the local newspaper wasted no time highlighting the role drunkenness had played in the violent affair. It came out that Dugan, who by all accounts had a sterling reputation and was traveling to Las Vegas on business, had dropped by Block 16 – the city’s Red Light District – earlier that day. While touring the dive bars where liquor and beer still flowed despite Prohibition, Dugan had fourteen shots of moonshine over a few-hour period. Around five or six that afternoon, he stumbled over to Fremont Street and wandered into Lambert’s Café where his fateful encounter with Marcus Wherle would occur.

The role of booze in the local community wasn’t the only centerpiece of the Dugan trial. The Nevada legislature had recently voted to mandate that women be included in local jury pools. This led to the first women jurors in Las Vegas’s history serving during the trial of Nick Dugan. There was a considerable amount of concern among local Vegas attorneys, who worried that women would be unable to justly decide a case involving an “attractive or magnetic” man like Nick Dugan.

Dugan testified at his own trial, alleging that he did not recall anything after about five o’clock in the afternoon of November 22nd. The last thing he remembered was taking a shot of moonshine in the back of one of the dives along Block 16 – the next thing he knew he woke up in the local jail. Guards at the jail and a local doctor supported Dugan’s version of events by noting he had been violently ill after regaining his senses at the city jail, likely from alcohol poisoning. Meanwhile, Clark County District Attorney Harley Harmon showed no mercy toward Dugan and argued for the death penalty. He sought to make an example of the young man, with an aim to show that illegal drunkenness would no longer be an excuse for violence.

Defeating the concerns of the entirely male local bar, the women of the jury urged a conviction of second-degree murder due to the wanton nature of Dugan’s crime – after all, he had discharged a firearm in a crowded restaurant after inviting Wherle to do something to stop his abusive behavior. After over five hours of deliberation, the men of the jury apparently convinced their fellow jurors to return a verdict for voluntary manslaughter due to Dugan’s extreme state of intoxication and lack of memory of the homicide.

Dugan only served about three years in the Nevada State Prison before being released on parole. The Las Vegas Age newspaper continued to rail against the evils of “Demon Alcohol.” And all the while, Las Vegas residents by and large continued to have easy and ready access to alcohol for the remainder of Prohibition and beyond.