downtown siege:

nevada’s most dangerous criminal and a hostage crisis at the vegas jail

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve had a criminal bent. When other kids were going to a school sock hop or something, I was out robbing an ice cream truck.”

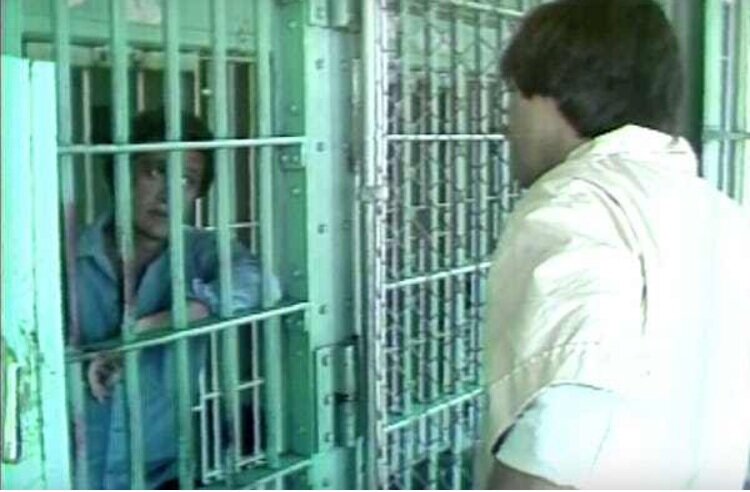

Patrick McKenna (L) - the man dubbed “Nevada’s Most Dangerous Criminal” - conducts a jailhouse interview. McKenna was convicted of murder, multiple sexual assaults, robbery, kidnapping, and several escape attempts.

seeking freedom by bargaining with the devil

On a hot summer day in 1979, two inmates of the Las Vegas City Jail attempted a bold escape. But a fatal flaw in their plan was seeking the assistance of a man reputed to be Nevada’s most dangerous criminal – Patrick McKenna. A deadly siege would result in surprising legal battles and give rise to the unanswered question of whether McKenna was the product of a dehumanizing childhood and penal system or just born bad.

Local press extensively covered the takeover of a jail annex located on the second floor of the Las Vegas City Hall, including law enforcement efforts to create a perimeter around the complex. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

jail break

Felix Lorenzo and Eugene Shaw were stifling inside their four-man cell at the Las Vegas Jail Annex on August 25, 1979. Unlike most jails that are standalone buildings, the Las Vegas Jail Annex was located on the second floor of the ten-story semicircular concrete slab with a glass face that served at the Las Vegas City Hall, with the mayor’s office at the apex and the offices of various other city officials and agencies occupying the floors beneath.

Shaw and Lorenzo were let out of their quarters in cellblock 5F, where the highest security prisoners were maintained, and provided with mops and buckets to clean the corridor floors. Lorenzo was facing an upcoming trial for a recent hostage incident that had earned him the moniker “The Nut Hut Bandit,” while Shaw was being held on robbery and drug offenses. Corrections Officer (C.O.) Robert Hansen stood guard over the group of inmates on the work detail.

As he swirled the mop along the jail floor, Shaw asked Hansen to replace a bucket of dirty water. The guard leaned over to pick up the bucket from the floor. As Hansen opened the door leading from the cellblock to the rest of the jail complex, Shaw offered a helping hand.

The attack by Shaw was so sudden that Hansen was caught by complete surprise. The prisoner grabbed hold of the corrections officer and held his hand over Hansen’s mouth to muzzle any cries for help.

Lorenzo dropped his mop and joined his compatriot in the assault on Hansen, with both men landing several blows on the guard and bringing him to near unconsciousness. Then Lorenzo, who had masterminded the escape effort now underway, grabbed a set of keys off of Hansen and made his way through the open cellblock door, rushing down the corridor to execute the next critical part of the plan.

Three guards were taken hostage by prisoners Patrick McKenna, Eugene Shaw, and Felix Lorenzo. The guards were handcuffed to cell doors to act as human shields in the event police raided the jail annex. Local press in Las Vegas covered the backgrounds of both hostages and captors. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

uncaging mckenna

Lorenzo sneaked past C.O. William Melton as he viewed a series of security cameras on a television monitor in a room off of the hallway. The inmate would have been trapped within the jail complex were it not for the efforts of William Medberry, a 27-year-old prisoner held on burglary and weapons charges. Earlier in the day, Medberry had left slightly ajar a door near the information area at the entry to the jail complex.

Behind the heavy door was an elevator and a gun locker. Lorenzo used the keys pilfered from C.O. Hansen to gain access to the locker and retrieved a 9 mm handgun. The ringleader doubled back and entered the information area. Leveling the pistol at the back of C.O. Melton’s head, Lorenzo demanded his surrender. The inmates now had a second hostage.

Lorenzo forced the surrender of another C.O., David Murray, as he made his way through the jail complex. Meanwhile, Shaw opened the door to one of the cells on cellblock 5F to release one of the fellow architects of the mayhem that had transpired over the last few minutes – 31-year-old Patrick McKenna.

McKenna was in his most familiar setting. He first ran into legal trouble at age 13, spending all but a few months of his adult life in the Nevada corrections system. And this was not his first attempt at a prison escape.

But while McKenna may have been able to provide valuable insight and muscle to Lorenzo and Shaw, these services came with a caveat – he was also a vicious sociopath unwilling to surrender control.

McKenna’s father was caught up in 1960’s labor wars in Las Vegas, which included charges of firebombing a cab from a non-union company that made local headlines. McKenna’s brother later recounted the routine childhood abuse Patrick suffered at the hands of their father. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

mckenna’s early years

Patrick McKenna was born in Colorado but moved with his family to Las Vegas at an early age. The young McKenna endured a childhood categorized by constant physical abuse at the hands of his father, Charles McKenna. The abuse was so routine that Patrick and his brothers grew up sleeping with sports equipment in their beds so that they had some way of defending themselves or their mother against their father’s rage.

The elder McKenna was a cab driver that became embroiled in a labor war in the late-60’s between union and non-union cab companies. In October of 1968, Charles McKenna rammed his car into a non-union cab parked in front of the Stardust. He ultimately had charges stemming from this incident dismissed by Justice of the Peace Roy Woofter, who found McKenna had no felonious intent and that the crash was likely the result of an accident.

Less than a month after dodging any consequences for the assault in front of the Stardust, McKenna was arrested for hurling two Molotov cocktails at a non-union cab parked at the Sahara Hotel. The younger McKenna seems to have adopted by habit or hardwiring his father’s violently impulsive propensities.

Spring Mountain Youth Camp, a facility for juvenile offenders located outside of Las Vegas. (Clark County)

molding a sociopath

Patrick McKenna had his first serious run into trouble with the law at age thirteen when he landed in the juvenile justice system for chronic truancy. The judge presiding over the case sentenced McKenna to eight months of incarceration at a facility for troubled youth. McKenna later told reporters that he actually enjoyed school but ditched as a form of petty youth rebellion, and what he really needed during this time was “direction and understanding.” Instead, the abuse suffered at home by the 13-year-old McKenna would pale in comparison to his tortuous stint at the Spring Mountain Youth Camp, a juvenile detention facility in the wooded mountains outside of Las Vegas.

The Spring Mountain Youth Camp of the 1960’s was a secluded black hole of horrors. The guards at the facility routinely forced the adolescent inmates to fight each other in gladiator-type matches, and the methods of punishment included being handcuffed to a flagpole outside in the freezing cold overnight. In addition to the physical abuse, former inmates alleged the facility had a reputation for turning a blind eye to chronic incidents of sexual abuse of the boys. According to McKenna, “The counselors used to beat the kids. There was no education. Just eight hours of hard work.”

The prospect that the youths at the Spring Mountain facility would be rehabilitated after their release was laughable – in fact, the exact opposite of rehabilitation was the more likely outcome. Most, if not all, of the boys sent to Spring Mountain by the juvenile justice system had experienced lives scarred by abuse and neglect. For boys already used to being hated or ignored, the abuse experienced at Spring Mountain only served to reinforce the rage, internal isolation, and distrust that are frequently the remnants of childhood abuse.

And for a boy like McKenna, already primed for anger and impulse control problems due to his violent upbringing, the months of unspeakable abuse at the Youth Camp only served to help mold a sociopath.

Sunrise Mountain, located on the east side of Las Vegas, as it appeared around the time of the brutal assault of a young couple by Patrick McKenna and a criminal associate. (UNLV Digital Collection)

mckenna the monster

Unable to adjust to school life after being released from Spring Mountain, McKenna felt like an outcast among his classmates. He continued to have disciplinary issues and went on to spend time in and out of other juvenile facilities, including one in Northern Nevada outside of Elko where he befriended several other boys. The friends by circumstance often passed the time trying to one-up each other with better plans for pulling off a burglary or car theft.

Within a short time after his release from the facility in Elko, McKenna was following in his father’s footsteps as a mob enforcer. McKenna and some of the young men he met in Elko formed a gang and contracted out to the organized crime elements that ran rampant in 60’s Las Vegas, earning money beating up people that didn’t repay their high-interest loans on time, performing burglaries, and acting as the muscle for corrupt elements in local unions.

McKenna’s budding criminal career escalated in grotesque fashion in 1964. On the night of July 9, 1964, McKenna and his friend, 19-year-old Hector Pacheco, drove to the house of a 17-year-old young woman they were acquainted with. The two forced the girl into the trunk of their car. Then they made their way to the home of another acquaintance, the woman’s 20-year-old boyfriend. McKenna and Pacheco forced the boyfriend into the car and drove out to Sunrise Mountain, which at the time was a desolate marker on the east edge of the Vegas Valley.

Once the kidnappers arrived at the secluded base of Sunrise Mountain, they forced their male victim out of the car and into the warm desert night. One of the captors walked around to the rear of the vehicle and pulled the teenage girl from the trunk. What followed was hours of sexual and mental torture at the hands of McKenna and Pacheco. The kidnappers subjected their victims to humiliating sex acts and beatings with boards and beer bottles. It was not until three in the morning that the malevolent duo drove away, leaving their victims nude and miles from the Vegas city limits.

Before daybreak, a police vehicle on patrol came to a sudden halt as the headlights illuminated a dazed and naked girl stumbling along the side of the road. The officer exited the vehicle and offered the battered survivor a blanket before bringing her to the patrol car. The young woman informed the police of what had happened and that her boyfriend was still lying nearby at the base of Sunrise Mountain. The victims were eventually able to provide the police the identity of their attackers.

Early on the morning of July 10, 1964, police arrived at the homes of McKenna and Pacheco to take both young men into custody. The crime shocked the small city and coverage of the criminal proceedings against the two were a consistent feature of the local press for the rest of 1964. In early 1965, only weeks before trial, McKenna took a deal with the District Attorney. He would plead guilty to rape charges against his two victims, and in exchange the State would drop the kidnapping charges that carried the potential of a life sentence. Pacheco refused a deal and proceeded to trial where he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

McKenna and several other inmates staged an escape from the Nevada State Prison in 1967. Nevada press covered the escape attempt and Governor Laxalt’s subsequent firing of the long-serving prison warden for permitting the escape to occur. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

escape attempts and brutality

Judge David Zenoff sentenced Patrick McKenna to a sentence of 5 to 15 years on the charge of rape against the teenage victim and a sentence of 5 years for “assault with intent to commit an infamous crime against nature” against his male victim. Judge Zenoff, perhaps because of McKenna’s young age, ordered the sentences to run concurrently rather than consecutively (Zenoff was instrumental in advancing reform of the juvenile justice system in Nevada).

In January of 1967, McKenna joined six other inmates in overpowering three guards at the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. McKenna and his accomplices donned the guards’ uniforms and acquired maintenance tools that they then used to break through the prison wall and perimeter fencing. But the inmates only managed to make it a grand total of a mile from the prison before all were tracked down and returned to their former quarters. Despite the rapid recovery of the inmates, Warden Jack Fogliani – who had served in that position since 1948 – was fired by Governor Laxalt only two days shy of his retirement.

Given the severity of his crimes and history of violent behavior, McKenna should have been away from society for his full sentence of 15 years. But, inexplicably, the by now hardened criminal was paroled in 1976. Within five days of his release, McKenna took a job to commit a hit in the Reno area, but instead of killing his target McKenna ordered the man out of town and sexually assaulted the man’s girlfriend. These crimes should have sent McKenna back to the Nevada State Prison for life, but the District Attorney did not pursue charges and McKenna was sent back to prison on a simple parole violation.

When the vicious sex offender’s prison term finally expired in 1978, McKenna was in his early thirties without a penny to his name or a place to call home. The ex-con returned to the only city he had ever known and soon struck up a friendship with two Las Vegas area sex workers. The women took pity on McKenna and offered to let him crash at their room at the Paradise Resort Inn.

Once again displaying his cold-blooded lack of empathy, McKenna responded to the women’s kindness by tying his two roommates together and sexually assaulting them, after which he threatened to kill them if they reported the crime. Not willing to remain silent, the women bravely defied their attacker’s threat and went to the authorities. McKenna was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to three consecutive life terms plus 75 years in prison.

McKenna’s crime spree upon his release from prison included multiple rapes and the murder of a cellmate. By this point, the Nevada press was well on its way to dubbing McKenna the State’s most dangerous criminal. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library/LVRJ)

pruno, chess, and murder

McKenna was housed at the Clark County Jail in downtown Las Vegas while awaiting transfer to his old home at the Nevada State Prison. January 5, 1979 was the start of the weekend and a rowdy atmosphere had overtaken the cellblocks at the jail – after all, Friday evenings were known as “party night” in lockup.

In one of the cells, McKenna and his fellow inmates were passing around a plastic bag containing “pruno,” a jailhouse alcoholic concoction brewed from fruit, yeast, and sugar while an episode of Midnight Special played on a TV in the background. One of the two other men sharing the cell with McKenna was burglary suspect 20-year-old J.J. Nobles, a drifter that took a position as a mechanic at the local Ben Stepman Dodge in Henderson where he allegedly burglarized several R.V.’s undergoing repairs. The young Nobles was unaware at this point in the night just how unlucky his cell assignment would turn out.

Sometime between 1 and 3 o’clock in the morning, the good times soured in McKenna’s cell. Witness accounts differed as to what led up to the altercation – an inmate across the hall said the dispute erupted when Nobles refused McKenna’s request to provide sexual favors, while an inmate sharing the cell with McKenna and Nobles said an argument during a chess match prompted the flareup. What is undisputed is that McKenna leapt at Nobles in a fit of rage and used a piece of cloth to strangle his cellmate to death.

After killing the man, McKenna got into his bunk and went to sleep.

The Las Vegas City Hall housed a jail annex on the second floor of the ten-story structure. This building now serves as the headquarters of Zappos. (Wikipedia)

siege: day 1

Transfer to the prison in Carson City was delayed for McKenna after he was charged for the murder of Nobles and entered a plea of not guilty. It was while awaiting trial in the Nobles case that McKenna crossed paths with Lorenzo and Shaw.

While the three ringleaders of the breakout plot had hoped to quietly sneak out of the prison after donning their guards’ uniforms, the plan for a lowkey escape was derailed within minutes of the first guard being subdued. As Lorenzo leveled a 9 mm at C.O. William Melton at the booking desk, a visitor to the jail spotted the assault through the window of the jail’s information desk. The visitor ran back into the elevator and alerted the detective’s bureau located in the same building.

Within fifteen minutes of the first guard being taken hostage, dozens of police officers – including two SWAT teams – were swarming the City Hall complex. Officers moved quickly to evacuate the rest of the offices in City Hall and stationed guards at every exit from the Jail Annex, with police snipers positioning themselves on nearby rooftops.

Realizing their plan for a subtle escape had been thwarted, the three ringleaders set about fortifying the jail. The captive C.O.’s were stripped and handcuffed to the bars of random cells in various corridors throughout the jail complex. Lorenzo, Shaw, and McKenna then pried open a gun locker to obtain a total of three handguns and a revolver. As for the other 84 prisoners in the jail at the time of the takeover, most remained locked in their cells except to perform tasks on behalf of their captors.

With the jail under their control, McKenna then used a phone to establish a line of communication with the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police to open negotiations. The hostage takers first demanded that Clark County Public Defender Tom Leen act as intermediary between the prisoners and police, but when Leen arrived on the scene McKenna refused to speak with the attorney. McKenna then demanded that Bob Stoldal, the news director of local station KLAS-TV, serve as the police point man during negotiations.

Terror gripped the captive C.O.’s while the negotiations transpired on and off throughout the day. McKenna repeatedly menaced the hostages, strutting by where the guards were chained, aiming his gun at their heads or groin, and threatening, “I’m going to blow your kneecaps off.”

List of demands issued by McKenna and his fellow hostage-takers as published in the local paper. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

The prisoners issued a list of eighteen demands for improvements in jail conditions. The hostage takers made it clear to authorities “they were ready to die” if their demands were not met. The police attempted to engage with some of the request for reform issued by McKenna, and they even reached out to local news outlets to explore airing the prisoners’ demands. But the haggling over conditions at the jail was merely a tactical shift, not a strategic one. The ringleaders were stalling until they could develop a plan to break free of their confinement.

Saturday concluded without a resolution and the hostage-takers still in control of the jail.

siege: day 2

As both sides settled into the siege, C.O. David Murray struck up a rapport with Eugene Shaw. Over the course of their conversations, C.O. Murray mentioned that his wife was pregnant. With McKenna’s repeated threats to kill or maim the hostages running through his head, Murray eventually asked his captor outright, “Any chance I’m going to survive?”

Negotiations carried on throughout Sunday. The hostage-takers were making some progress with the police in gaining concessions on improving conditions at the Clark County Jail. But amidst this progress there were growing tensions among the three ringleaders. Shaw was ready to start winding down the siege – after all, it was clear there was no longer a real possibility of escape without the risk of serious bloodshed. Not to mention, the 84 other inmates not part of the jail takeover were growing restless.

But McKenna, with a death sentence now hanging over his head, was not in the mood to negotiate for anything less than a chance at freedom. And Lorenzo, facing a 150-year prison sentence, sought to escape but also harbored a desire to exact revenge against the hostages for slights he suffered by them while incarcerated. McKenna developed a plan to up the stakes of the siege to improve the hostage-takers’ negotiating position.

Later that day, McKenna asked Bob Stoldal and his news crew to enter the first floor of City Hall where McKenna would meet them in the elevator to conduct an interview. When Stoldal ran the proposal by police commanders on scene, they quickly quashed the idea. And it was a good thing they did. Detectives would later discover a typed set of demands from McKenna and Lorenzo that included a request for a helicopter and amnesty for taking over the jail. Police determined that the two intended to take Stoldal and his crew hostage to facilitate their escape.

Sunday night concluded with the City Hall complex still under the control of the hostage-takers.

The jail annex siege ended in dramatic fashion. Newsman Bob Stoldal sat stunned as gunfire erupted while he was facilitating negotiations with McKenna. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ/AP)

firefight

Shaw had made the decision that he wanted to turn himself in and wanted to give himself space to do so. Over the night, Shaw convinced McKenna that one of the C.O.’s should be released as a sign of good faith and to buy time to continue efforts to escape.

Around 5:30 a.m. on August 27, 1979, Felix Lorenzo got wind of the plan to release a hostage. Lorenzo had made the decision that he would escape or die trying, and that in any case, he did not intend to allow any of the C.O.’s to leave the jail alive. In the presence of Shaw, Lorenzo uncuffed C.O. William Melton and ordered him to stand up. Lorenzo planned to execute the C.O. before he could be released.

Shaw knew Lorenzo’s intent. A shot rang out. Shaw fired at Lorenzo to prevent him from killing the guard, but he had missed. C.O. Melton darted out of the way and took cover behind a nearby desk. Lorenzo drew his sidearm and returned fire at Shaw, striking him several times. A ricochet struck C.O. Melton through his hand as the shootout continued. Shaw ultimately took better aim than with his initial shot and landed a round in Lorenzo’s chest that sent the man collapsing to the ground where he lie motionless.

Shaw knew that ending the siege meant taking down McKenna. Before Shaw confronted his co-conspirator, he went to where C.O. David Murray was chained to a cell door. Remembering their prior conversation, Shaw picked up a mattress and placed it over Murray, instructing the young father-to-be, “Tell your son I did this and put a rose on my grave.”

McKenna was on the phone with Stoldal engaging in further negotiations when the firefight between Lorenzo and Shaw broke out. Shaw charged the sergeant’s office and exchanged gunfire with McKenna. Shaw was hit eight times in total and succumbed in short order from his wounds.

SWAT teams waiting outside of City Hall breached the complex at the sound of gunfire. Bill Stoldal listened – stunned – as shots rang out on the other side of the line. He had remained hopeful until the end that he could assist in resolving the standoff. One of the inmates not involved in the siege followed police instructions over the phone to open the secured doors to the jail.

SWAT officers ordered every inmate to strip to their underwear before being escorted out of the jail. McKenna took up position next to C.O. Murray, who he used as a shield against advancing SWAT officers. After a few tense moments, Murray was able to convince McKenna to surrender his weapon. An uninjured McKenna was taken into custody and held under tight security at the Clark County Courthouse.

McKenna ultimately stood trial for the murder of J.J. Nobles after the conclusion of the jail annex siege. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

the trial of mckenna’s life

The following year, McKenna stood trial for the murder of J.J. Nobles. The trial took place under a heavy blanket of security in light of McKenna’s propensity for attempting violent escapes, with five armed guards present in the courtroom and a SWAT team waiting in the courthouse.

McKenna was defended by Mike Cherry, who would later go on to serve as a justice of the Nevada Supreme Court. Cherry argued that his client should not be convicted of premeditated first degree murder because the killing of Nobles had been due to an “emotional impulse” after Nobles took a swing at McKenna while the two were inebriated.

Clark County District Attorney Mel Harmon sought the death penalty for the murder of Nobles, arguing to the jury that McKenna “killed a man, without feeling, maliciously and with premeditation.”

The jury was unpersuaded by the defense theory of the case and returned a verdict of guilty. McKenna took the stand to testify during the penalty phase of the trial in an effort to convince the jury to spare his life. He relayed tales of the horrors suffered at the Spring Mountain Youth Camp, but he refused to discuss the routine abuse administered by his father while growing up. Even facing execution, McKenna could not bring himself to confront his violent upbringing.

McKenna sat stoically as the jury sentenced him to death in the gas chamber. He received an additional 92 year sentence for his role in the takeover of the Jail Annex.

Nevada State Prison where McKenna and a fellow inmate took several hostage amidst an escape attempt in 1981.

“i’m ready to kill or be killed”

McKenna was transferred to the Nevada State Prison at Carson City after his sentencing. It was not long before the dead man walking staged another attempt to gain his freedom.

On the night of February 14, 1981, McKenna was being led back to his cell on death row by a solitary guard. The guard opened the cell door and turned to confront a .38 pistol being leveled at him by a smirking McKenna. The pistol had been concealed in the prison complex for more than a year before McKenna was tipped off as to its location.

McKenna ordered his captive to open the cell of another inmate that had helped hatch the escape plot, attempted murderer David Wayne. Wayne and McKenna then disarmed three other guards and captured prison nurse Nelda Cushman. The escaped inmates incapacitated the four guards and locked them in a plumbing maintenance room. They then used Cushman as a decoy to lure a shift sergeant near enough to be captured and subdued.

Wayne and McKenna pilfered two walkie-talkies from the captured guards before exiting their cellblock into the prison yard. The escapees sprinted in opposite directions across the open yard, seeking to avoid the gaze of the prison watchtowers and maintaining communication with each other via the walkie-talkies. Wayne took Cushman with him and barricaded himself in a cell house area with his hostage. McKenna entered another cellblock as he scoured a route to break free of the prison grounds. In the course of his search, McKenna managed to seize three additional guards.

Frustration set in as McKenna realized the alarm had been raised and his chances of escape decreased with every second that Carson City Sherriff SWAT teams drew closer to the prison complex. Just as in Las Vegas two years prior, McKenna had managed to glimpse freedom before witnessing it slip away with the ring of a phone from police negotiators. Prison Superintendent Max Neuneker strapped on a bulletproof vest and entered the prison grounds to speak with McKenna, where he made it clear to the cornered prisoner that while authorities obviously wanted to avoid a loss of life among the hostages, there was no scenario under which McKenna was leaving the Nevada State Prison alive.

Despite McKenna threatening police that he was ready “to kill or be killed,” he surrendered once he concluded escape was impossible. McKenna was not suicidal. He preferred to carry on his fight in the Nevada courts challenging his death sentence rather than engaging in a doomed battle with the police.

And his fight was successful to an extent. McKenna obtained the overturning of his death sentence on the grounds that certain aspects of the death penalty statute were vague. On retrial, McKenna was again sentenced to death. McKenna won yet another appeal that saw the overturning of his death sentence. In 1996, McKenna again faced retrial and was again sentenced to death. His appeal of this third death sentence to the Nevada Supreme Court in 1998 based on the security measures taken during the proceedings was denied.

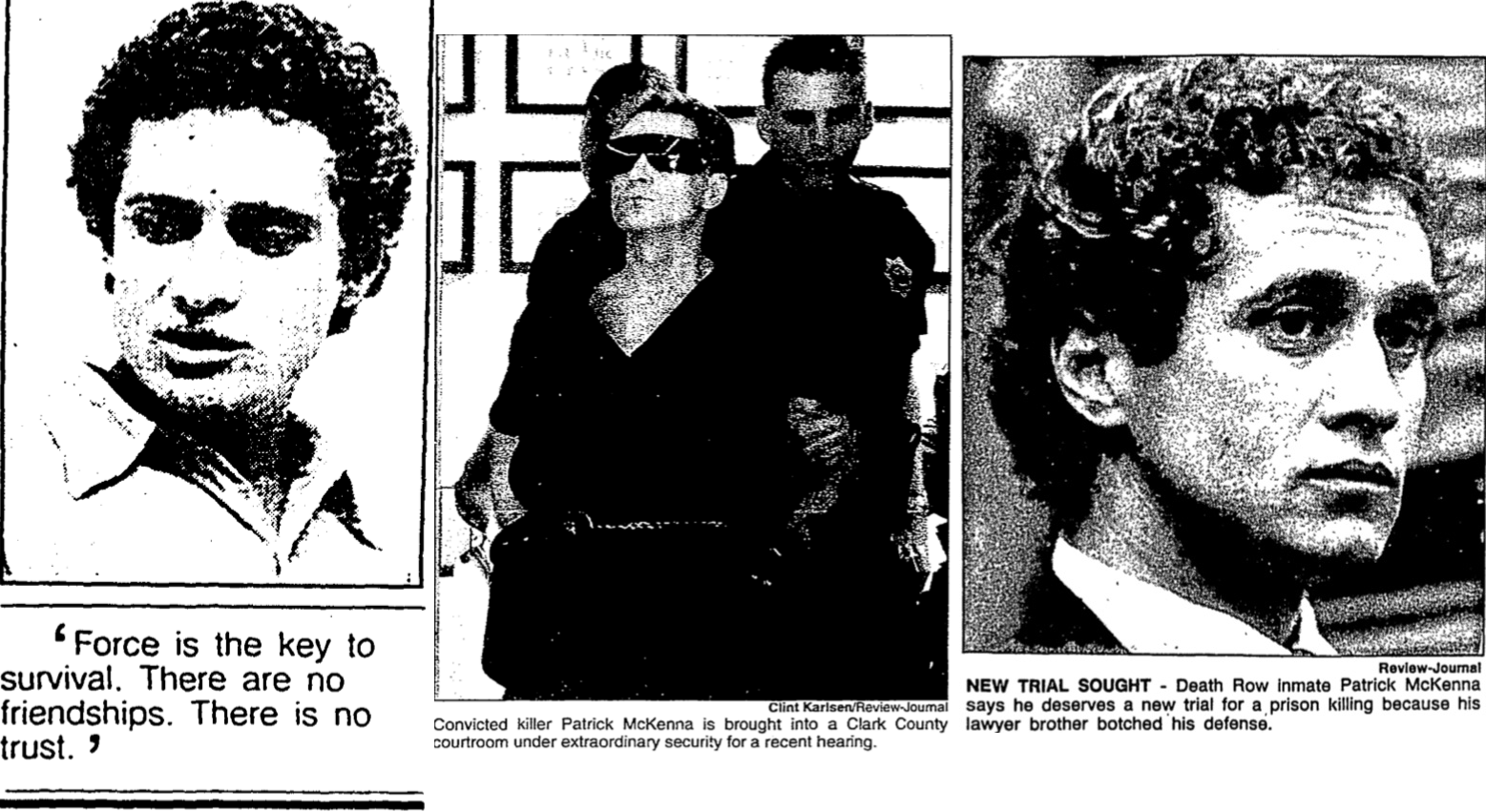

Patrick McKenna’s decades-long legal battle to fight his death sentence, coupled with his willingness to serve as an articulate interview subject, led to consistent coverage of his case by Nevada press. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

“I regard the system as my enemy”

Patrick McKenna spent his entire adult life – save for a few months – within the confines of the Nevada corrections system. In a jailhouse interview with a reporter years after the jail siege, McKenna pondered what had led him to become “Nevada’s Most Dangerous Criminal.”

The inmate offered that his involvement with the criminal justice system since his youth had alienated him from the ability to become a part of society. “I can’t function out there,” McKenna told the reporter. “I regard the system as my enemy. I resent what it’s done to me and what it did to my life.” McKenna went on to say of prison life, “Force is the key to survival. There are no friendships. There is no trust.” McKenna compared the way long sentences with no real efforts at rehabilitation turned men such as himself into a “stone cold criminal” just “like an assembly line at Ford.”

Relatives that testified on behalf of McKenna in an effort to spare him the death penalty noted the harmful impact that experiencing routine childhood abuse by his father had on his development. The trauma McKenna suffered in his youth at the hands of his father no doubt contributed to making him the monster he became. But McKenna also had four brothers that witnessed the same abuse and managed to lead normal lives. In fact, one of those brothers was Ken McKenna, who went on to become an attorney and acted as his brother’s defense counsel during ongoing litigation of Patrick’s convictions during the 80’s and 90’s. But sociopaths are not renowned for reciprocating empathy - McKenna would later file an appeal alleging a poor courtroom performance by his brother led to his conviction.

McKenna wasn’t born a monster - or if he was, there were at least glimmers of humanity that occasionally shined through. Patrick McKenna’s siblings recounted how their brother would refuse to strike back at their father no matter how vicious the beating he suffered because Patrick wanted to be better than his old man. But Patrick manifested a disregard for rules and embrace of cruelty that was absent in his brothers at an early age. McKenna said, “As far back as I can remember, I’ve had a criminal bent. When other kids were going to a school sock hop or something, I was out robbing an ice cream truck.” And McKenna’s own assessment of whether he was born or made into a hardened criminal was clear - “People can be born with a deformity such as a twisted arm or a bent finger,” he said. “Why can’t a person be born with a bent conscience?”

McKenna was biologically primed for the violent life he lead, and, at a certain point, he was too far gone to transform into anything other than what he had become. McKenna said during a 1989 interview, “If I left prison tomorrow, my only goal would be to become a smarter criminal to avoid ending up in prison again. I’m a realist…I have no skills except criminal skills.”

McKenna remains awaiting execution, the longest serving inmate on Nevada’s death row.