bigotry and a bomb blast

“We’re not going to move. I’m just as particular as other people about where I want to live.”

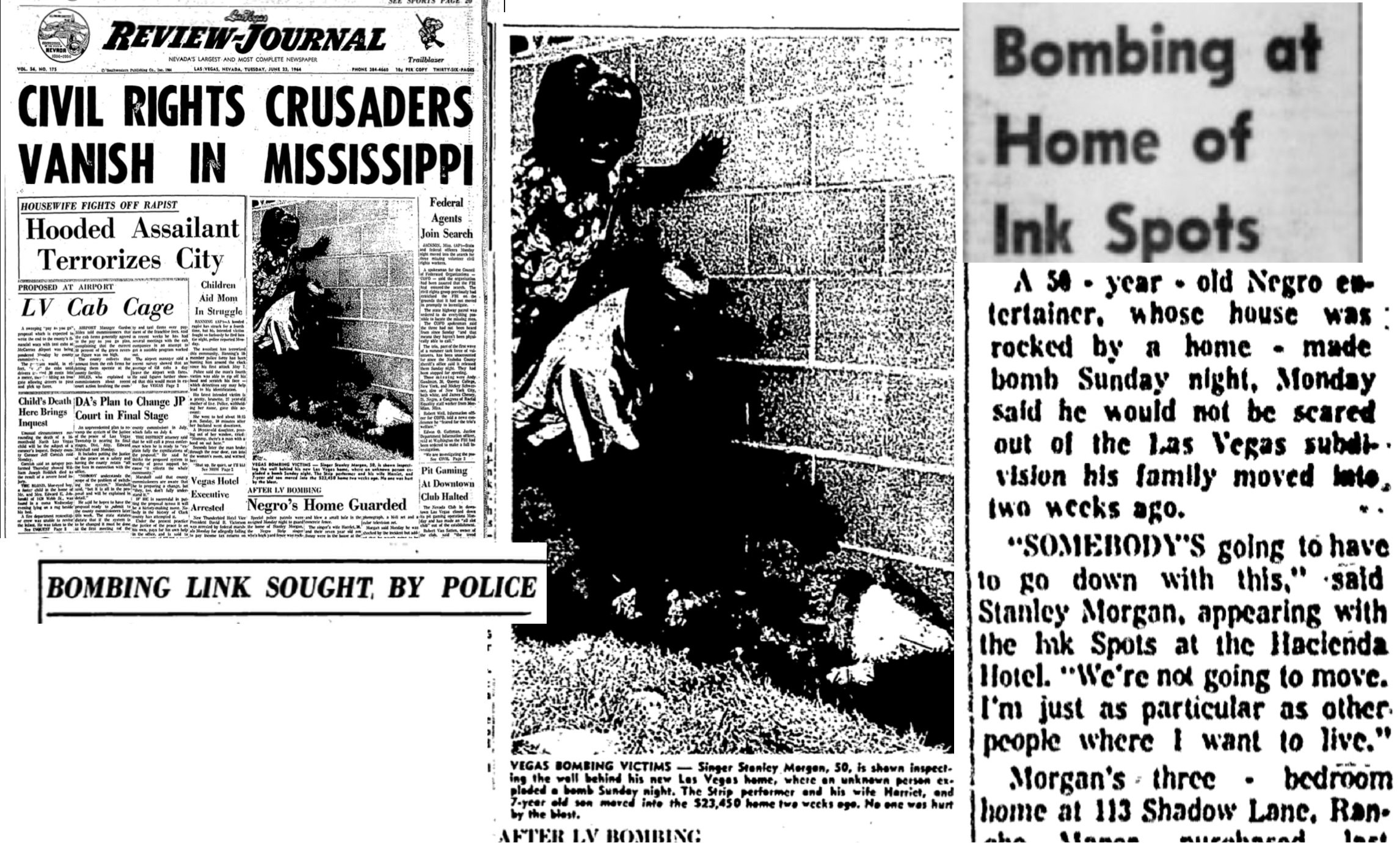

A white supremacist terror attack against Strip entertainer Stanley Morgan, leader of the band The Ink Spots, generated heightened coverage in the local and national press due to the recent disappearance of three civil rights workers in Mississippi. Morgan’s home was bombed in 1964 shortly after he moved his family into an all-white neighborhood of Las Vegas. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/UCR/LVRJ/UPI)

racial violence in 60’s vegas

The 1960’s saw a national wave of white supremacist terrorism targeting Black Americans as part of the backlash against the gains of the civil rights movement.

Sadly, Las Vegas was no exception.

Representatives from the NAACP and city leaders of Las Vegas meet at the Moulin Rouge in 1961 to reach an agreement to desegregate the Strip and downtown casinos. (UNLV Digital Collection)

the mississippi of the west

Las Vegas has an ugly history of legal and de facto segregation that persisted for decades. After a period of relaxed racial attitudes during the first years after the city’s founding, tensions started to rise during the 1920’s as the Ku Klux Klan experienced a nationwide resurgence. White supremacist violence came to the center of Las Vegas in 1924 when a KKK march took place on Fremont Street, followed by a cross-burning. A few years later, there was anticipation of a hiring boom fueled by federal money with the announcement that construction would being on the Hoover Dam. The NAACP established a Las Vegas branch in response to the KKK presence in the city and to advocate for fair hiring practices for the Hoover Dam project.

The push for segregation by business and city leaders increased with the establishment of legalized gaming in 1931. The city’s casinos began to attract plenty of tourists from Texas and the South where Jim Crow had been entrenched since the end of Reconstruction. And by the 1940’s the bigoted attitudes of the mob-connected owners of the casinos sprouting up along the Strip and downtown worked to create a de facto system of racial segregation in Las Vegas’ main industry.

The denial of equal opportunity gained legal support when the Las Vegas City Council began denying the renewal of business licenses to Black-owned businesses starting in the 1930’s, though Council members noted approval would be granted if Black-owned businesses were relocated across the railroad tracks to the “Westside” of Las Vegas. The roads in the Westside were unpaved and it lacked sewer or public services available to the rest of Vegas. The use of licensing to force Black business owners to relocate to the Westside, coupled with restrictive covenants and redlining that largely prevented integration of residential neighborhoods, led to most Black Las Vegans being forced to reside in the Westside by the 1940’s.

A March, 1954 issue of Ebony magazine dubbed Las Vegas the “Mississippi of the West” due to the blatant code of racial segregation implemented in the city. A strong local NAACP branch fought for the integration of casinos and neighborhoods, as well as fair hiring practices in the lucrative gaming industry. This eventually led to a sit-down with civil rights leaders at the Black-owned Moulin Rouge hotel located on the Westside where city and business leaders agreed to end discriminatory bans on Black patrons and entertainers at Vegas hotels and casinos. This was followed up with a 1971 consent decree designed to combat segregation in neighborhoods and schools in the city.

But like many other places in the country, these steps toward eliminating the effects of bigotry were met by violence.

Stanley Morgan, victim of the bigoted attack on his home, pictured with his Ink Spots, a regular Vegas act of the 1960’s. (UNLV Digital Collection)

an explosion rips the night

For two years in the early 1960’s, Stanley Morgan led the all-Black band The Ink Spots as the group played regular shows at the New Frontier. In 1964, Morgan and The Ink Spots changed venues and began a residency at the Hacienda hotel and casino, joining other Strip regulars of the time like Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and Fats Domino. Not long after starting his run at the Hacienda, Morgan purchased a house in the all-white Rancho Manor neighborhood of Las Vegas and moved into the home located at 113 Shadow Lane with his wife and young son.

The thunderous crack of an explosion startled awake the residents of Rancho Manor on the night of June 21, 1964, including Harriet Morgan. Stanley was performing at the Hacienda when the blast occurred, so Harriet rushed out her front door to inspect the source of the noise, encountering several of her neighbors already filling the street and making their way toward her home. Realizing the explosion had taken place in close proximity, she entered the backyard and discovered an eighteen-inch hole blown through the six-inch concrete wall surrounding the yard of her residence.

The explosion had been loud enough to be heard over a mile away at the headquarters of the Las Vegas Police Department. Several detectives on duty responded to the blast and arrived at the Morgan residence within five minutes.

Police determined that the explosion was caused by a bundle of dynamite placed against the rear wall of the home, and the blast could have easily killed or seriously injured someone had Morgan’s family not been asleep in the house at the time of the bombing. Unfortunately, there was little information for police to go on as the bomber had lurked through the desert outside of the Rancho Manor subdivision while cloaked in the shadows, leaving no eyewitness descriptions of a potential suspect.

Twenty minutes into Stanley’s first show, he was called off the stage to receive a phone call informing him his house had been bombed. Stanley rushed home to ensure his family was safe, and he returned to the Hacienda to finish the last show of the night only after Bob Bailey, the chairman of the Nevada Equal Rights Commission, promised to have a friend watch Stanley’s home for the remainder of the night.

Several of the Morgans’ neighbors in Rancho Manor offered to let Harriet and her son stay the night at their homes if she was frightened of a further attack, but Harriet was determined to stay the night in the home from which an unknown terrorist had tried to force her.

The bombing of Stanley Morgan’s home shocked many in the Vegas community. The Las Vegas-Review Journal published an editorial lamenting the attack and calling for action to prevent the spread of further racially-motivated attacks. For his part, Morgan refused to bow to intimidation and continued to live with his family at the residence on Shadow Lane. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District/LVRJ)

standing firm

The bombing of the Morgan residence occurred on the same day that three civil rights activists - James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner - were murdered in Mississippi while registering Black voters across the state. The Mississippi case drew national attention and heightened attention on the attack targeting the Morgan family. The Las Vegas police turned the case over to the FBI within days, but they fared no better than police detectives in locating a suspect. Police conducted regular patrols around the Morgan residence in the days following the bombing to ward off any further attacks.

The attack shocked the community. The Las Vegas Review-Journal published an editorial a few days after the bombing entitled “A Tragic Realization - It Can Happen Here” calling for action to prevent any further such racist violence. “[W]e have the first sign of an extremely dangerous attitude and the making of an explosive atmosphere which must be corrected now.”

Harriet Morgan told the press, “We asked people what kind of town this was before we came here to live. And they told us it was a pretty good town and liberal. We can’t understand this.” The Morgans noted that they had never encountered problems during the two years they resided at the predominantly white Mansion Manor apartments near the Convention Center.

Stanley Morgan stood firm after the bombing, telling reporters he would not be intimidated. “We’re not going to move. I’m just as particular as other people about where I want to live.”

Sources:

African Americans in Las Vegas

Las Vegas' Westside Began As Townsite On Other Side Of Tracks