Always Pay Your Hitman

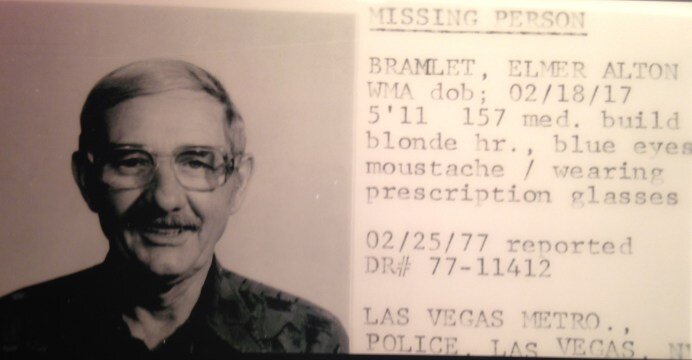

Al Bramlet, head of the powerful Culinary Union in Las Vegas, was abducted from McCarran Airport in 1977.

Las Vegas in the 1970’s was the site of bombings and murders, but not all of this mayhem was linked to the mafia. A labor dispute between the Culinary Union Local 226 and several off-Strip restaurants escalated into violence starting in the fall of 1975, which ultimately resulted in the head of the Culinary Union learning a valuable lesson – never refuse to pay a hitman.

Two bombs placed on the roof of the Alpine Village Inn restaurant on December 20, 1975, jeopardized the lives of nearly 400 patrons and employees. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

BOMBING AT THE ALPINE VILLAGE INN

Al Bramlet arrived in Las Vegas from southern California in the 1940’s to organize restaurant and casino workers. Over the course of several decades, Bramlet forged the local Vegas Culinary Union into one of the most formidable labor organizations in the nation. But there still remained holdouts against the Culinary Union in 1970’s Vegas.

The Culinary Union had been engaged in years of informational picketing outside of several off-Strip gourmet restaurants and taverns in an effort to organize their employees. In some cases, such as with the high-end restaurant the Alpine Village Inn, the union had been picketing for almost twenty years. The frustration by union leadership over the inability to bring these restaurants into their fold was compounded when employees at several Culinary restaurants voted to decertify the union or to form independent bargaining units, weakening Culinary’s power.

The first sign these tensions would boil over into violence was in September of 1975 when a small but powerful bomb detonated in an employee locker behind the Alpine Village Inn. Police later discovered another bundle of high explosives that failed to detonate attached to the restaurant’s air conditioning unit along with two smoke canisters. Investigators posited the second bomb was intended to send smoke through the shattered air ducts and into the dining area.

Only three months later, the Alpine Village Inn was struck again. On the night of December 20, 1975, as over 300 patrons and 70 staff occupied the building, a bomb tore through the roof of the restaurant near the kitchen, leaving a hole over two feet in diameter. Thirty seconds later a second bomb ignited on the roof, sending more debris into the kitchen area. The bombs caused a fire to break out, but nevertheless everyone inside the restaurant was able to make an orderly exit without injury. The lack of loss of life was miraculous – investigators determined that one of the two bombs had nearly ruptured a gas line, which would have instantly reduced the entire building to rubble.

Another gourmet restaurant, David’s Place, was struck by a bomb just a month after the Alpine Village Inn attack. Local press closely followed developments in the bombing investigation. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

ANOTHER RESTAURANT HIT

Las Vegas did not have long to recover. The next month, another sudden explosion thundered through the pre-dawn air about a mile west of downtown Vegas on January 12, 1976. The target of this blast was David’s Place, a gourmet restaurant that had long resisted efforts at unionization. Officers having coffee a few blocks away thought the sound of the blast was their waitress dropping a pile of dishes. When the officers realized what the sound was, they drove to the scene of the bombing where they encountered thick white smoke billowing across Charleston Boulevard.

David’s Place was left in ruins. In fact, the bomb was so powerful it sent a light fixture at a nearby bank careening to the floor and shattered windows in a half-dozen buildings. Several people at a residential facility for the elderly next door to David’s Place were injured by flying glass. Police investigators determined that the blast had been caused by high explosives left at the rear of the gutted restaurant.

No suspects were arrested in connection with the bombings. A spokesman for the Culinary Union denied any involvement with the blasts and offered the organization’s support for the investigation. The owner of David’s Place rebuilt his restaurant, and the union pickets returned after the grand re-opening.

Things remained quiet for the next year.

The bombers engaged in a dangerous escalation that ultimately failed in January of 1977. The inability to locate suspects in the attacks was a focus of press accounts after the double bombing attempt. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

ESCALATION

Then on the night of January 24, 1977, the culprits behind the previous bombings engaged in a dangerous escalation. Raymond Kraber, a security guard patrolling the parking lot outside of the Village Pub, another non-union restaurant located a few blocks east of the Strip, noticed a puddle of gasoline beneath a jeep parked near the building. Upon closer inspection, the security guard saw there was a steady drip of gas coming from beneath the vehicle. His suspicions aroused, the guard called the police.

The dispatcher assumed this was a call for a routine “gas wash” and the fire department was dispatched to hose down the area. But the responding firefighters inspecting the jeep noticed a barrel with tubing connected to it in the rear of the vehicle and realized this was no routine call. The bomb squad was summoned to the scene and determined they were dealing with a sophisticated device. The barrel in the rear of the jeep contained about 350 pounds of gasoline, with a slow drip from the barrel fed via a tube allowing it to saturate the interior of the vehicle and the ground beneath to create the conditions for a rapid ignition. The unlocked doors of the jeep had been rigged to a flash detonator so that the first unsuspecting person to open the door would trigger a massive explosion.

As the bomb squad and firefighters worked to defuse the bomb at the Village Pub, a call came in from another guard working security at the non-union restaurant Starboard Tack after spotting a suspicious jeep in the parking lot with gasoline dripping from the undercarriage. First responders arriving at Starboard Tack determined they were dealing with a device identical to the one left outside the Village Pub.

The only injury caused by the improvised explosive devices was to fire marshal Tom Huddleston, who suffered burns when an ignition device he was removing from a jeep went off in his hands and set his shirt alight. The fire marshal likely would not have survived had the device detonated a few moments earlier while being removed from the jeep. Huddleston later commented, “I lost a good shirt, but it makes you appreciate the small things in life.”

The bombings terrorizing non-union restaurants across Las Vegas had allegedly been ordered by Al Bramlet as an extralegal means of increasing his union’s bargaining power. Tom and Gramby Hanley, a father-son hitman team whose handiwork by this point had already left a bloody trail across Las Vegas, were hired to place the bombs. When Bramlet first hired the duo to carry out the bombings, Gramby Hanley used a connection at a local mining company to purchase several hundred pounds of high explosive under-the-table.

Bramlet paid the Hanleys tens of thousands of dollars for the bombs from the union fund, with the payments made to Oasis Air Conditioning – a front company run by Tom Hanley. The relationship between the Hanleys and Bramlet had run along smoothly until the failed twin bombings at the Village Pub and Starboard Tack. Bramlet had agreed to pay a total of $17,000 for the two bombings, $7,000 up front and the rest due upon completion of the job. But after both bombs failed to go off, Bramlet refused to pay the remaining $10,000 to the Hanleys.

The Hanleys were not one to be stiffed on money they felt was owed. From their perspective, they had taken the risk to build and place the bombs – it wasn’t their fault both security guards decided to call the cops instead of inspecting further and triggering the devices. And it would set a bad example in their line of work to allow a contract to go unpaid.

But while the Hanleys wanted to settle their score with Bramlet, they also wanted to avoid unnecessary risks to their safety. It was widely known that Bramlet always carried a .357 revolver on his person in case one of his many enemies tried to do him harm. It would be preferable to deal with Bramlet without worrying about him shooting back, and the Hanleys had a plan to confront the union boss at a place they knew he would be unarmed.

The Bramlet disappearance captivated the local and national press for several weeks. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

ANOTHER JIMMY HOFFA

Bramlet flew into McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas on return from a trip to Reno on union business on the afternoon of February 24, 1977. The Hanleys knew that Bramlet would be unarmed upon returning from his flight back to Vegas – a spate of “skyjackings” in the early 70’s had resulted in some of the first uniform bans on weapons aboard aircraft.

Bramlet disembarked from his plane shortly before 4:30 p.m. and called his daughter from a payphone to tell her he would be home in about thirty minutes before joining dozens of other travelers making their way through the terminal to the airport exits. Bramlet was jarred from his present concerns when he spotted two familiar faces waiting for him in the crowd. The Hanleys gave Bramlet a wave and approached. Bramlet’s heart sank as the reality set in that he had nowhere to run. He entertained hope that he would be able to sort things out with his former associates.

“Let’s go for a ride, Al,” Tom Hanley said to the man he had often crossed paths with over the past few decades.

Al Bramlet walked with the Hanleys out of the airport and into a nearby parking garage. The trio made their way to a van that was occupied by Clem Vaughn, another former associate of Hanley’s from his days running the sheet metal workers union. Bramlet was handcuffed and gagged in the back of the van before the vehicle exited the parking garage. The van took a few turns before finding its way to Blue Diamond Road. From there, as the sun began to set, the van continued on its journey into the wide-open desert.

Once they were well outside the Vegas city limits, the Hanleys made a stop at one of the few signs of civilization in the middle of the desert – an isolated payphone. Bramlet was ordered out of the van and instructed to call an executive he knew at the Desert Inn Casino to demand $10,000 for a “loan” and gave instructions for the money to be delivered to the Horseshoe Casino in downtown Vegas, which was owned by notorious gangster and gambler Benny Binion. Bramlet complied upon being assured by his kidnappers that he would be released upon paying the balance owed for the bombings. The Desert Inn executive hurried to get the money ready but no one ever arrived at Binion’s Horseshoe Casino when scheduled to pick up the “loan.”

It is uncertain whether the Hanleys ever picked up the $10,000 from the Horseshoe since they were known to perform some of Benny Binion’s more unsavory work around Vegas. But what is known is that the Hanleys did not keep their promise to release Bramlet. He was placed back in the rear of the van and the four men continued their voyage into the dark desert night.

The van made its final stop down a bumpy isolated desert road near Mount Potosi. Bramlet was taken from the back of the vehicle and his restraints removed. Tom Hanley exited the vehicle and took out a flask of whiskey. After taking a swig, he asked his old associate, “You want some, Al?”

“I think I could use a drink,” Bramlet replied. He accepted the flask and had a sip as Tom Hanley took a few steps in the opposite direction. Hanley then pulled a small-caliber revolver from his pocket and fired a single shot into the back of Al Bramlet’s head. The union boss collapsed at the height of his power alone along a quiet desert road. Hanley then emptied the rest of the revolver into Bramlet before the other men dragged the body a few yards away into a waiting shallow grave, hastily covering the corpse with rocks and debris.

Thus ended the all-powerful reign of Al Bramlet over the Vegas Culinary Union.

Learn more about the Labor Wars that rocked 1970’s Las Vegas at the link below: