boomtown: blowing up sin city

“Thanks but no thanks. That’s not my style.”

Thousands of bombs have gone off across the United States over the course of the 20th century for every reason from the personal, to the political, to the financial. And Las Vegas has not spared from the threat of criminal bombings.

News accounts of the 1972 bombing of a TWA airliner at McCarran International Airport focused on the need to increase airport security measures, which in many locales were lax by modern standards. For example, at the time of this bombing, McCarran Airport had no perimeter fence between public roads and the tarmac. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

an airport bombing

During the early morning hours of March 8, 1972, a Boeing 707 airliner sat taxied at passenger gate 10 of McCarran International Airport in view of the lights of the Las Vegas Strip. At 3:50 a.m. an explosion thundered through the cockpit of the plane, hurling debris and twisted metal across the tarmac from the starboard side of the aircraft. A small fire erupted before burning itself out, but there were no injuries as a result of the blast due to the early hour of the attack. Within hours, the plane was moved as far as possible from public view to avoid disturbing passengers.

The previous day an anonymous caller had phoned in a threat to bomb six TWA planes in one hour intervals if the company refused to pay a $2 million ransom. A bomb was discovered on March 7, 1972, in an attaché case aboard a TWA plane at JFK Airport in New York City only minutes before the device could detonate. Investigators believe the bomb that went off at McCarran Airport had been placed on the plane in New York City and that it had been missed when the craft was screened before arriving in Vegas. Police had been monitoring TWA craft at McCarran since the extortion threats came in and had set up a security perimeter around the airport.

TWA refused to publicly comment on reports that company executives were negotiating with the extortionists. Federal agents from various agencies worked across the country to identify any further potential bomb threats to passenger aircraft, and the general manager of TWA in Las Vegas noted the culprit was someone likely to “know his way around the industry” and “would have to know a considerable amount about the aircraft.”

Security measures were tightened at McCarran Airport after the bombing, including building a fence around the entire perimeter of the airfield – before the 1972 bombing it was possible to drive up to the tarmac from the roads surrounding McCarran. McCarran Airport also began issuing identification cards for employees and prohibiting anyone but passengers from gate areas.

No suspects were ever arrested or charged for the bombing in Vegas or the attempted bombing in New York.

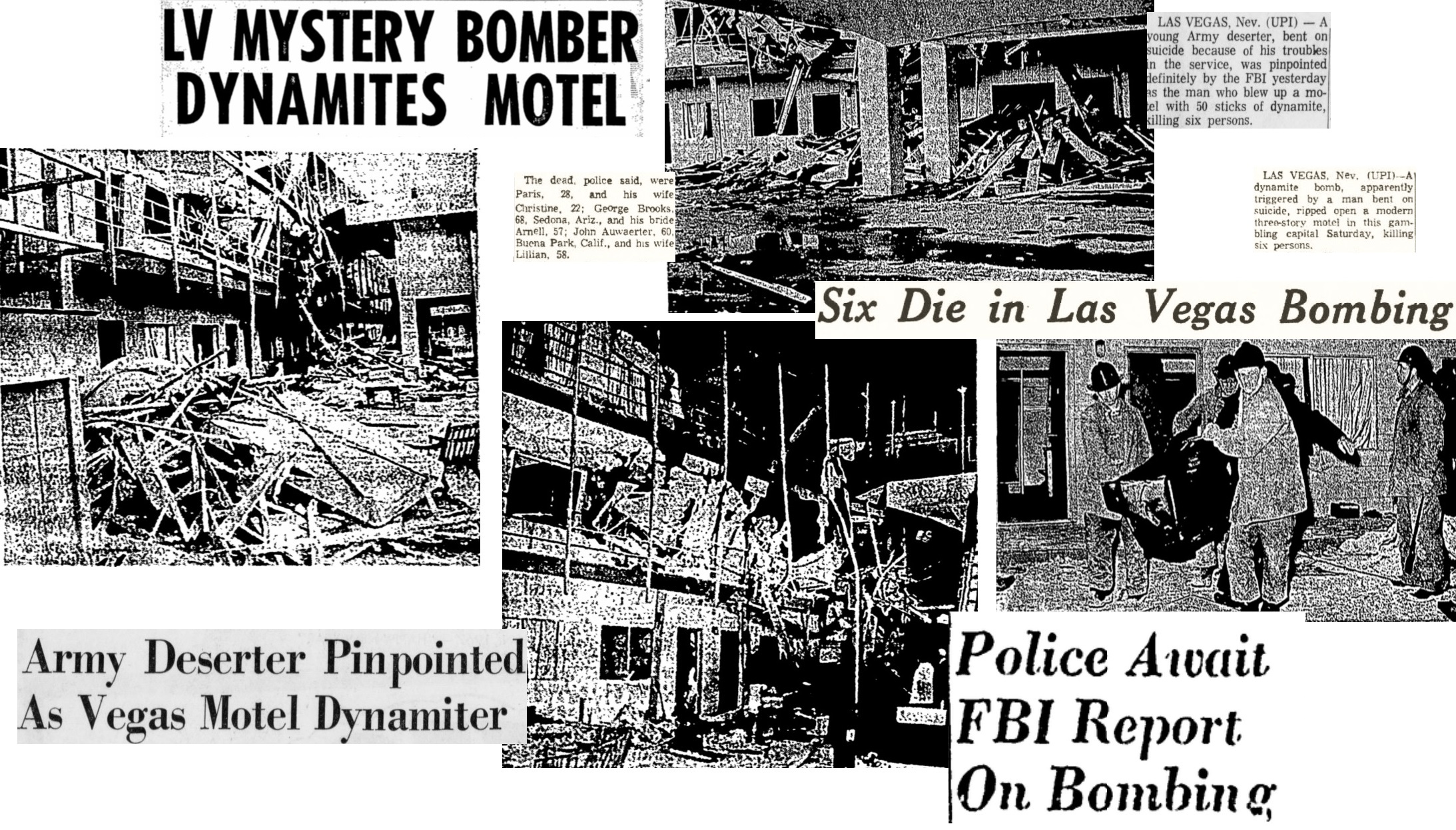

The bombing of the Orbit Inn Motel in 1967 by a deserter from the U.S. Army shocked the city of Las Vegas as it continued to develop its national reputation as the entertainment and vice capital of America. Local press followed the investigation into the still-mysterious motives of the bomber. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

An army deserter with fifty sticks of dynamite

Glitter Gulch – the unofficial name of the casino district in downtown Las Vegas – was still bustling with the weekend influx of tourists in the early morning hours on January 7, 1967. Patrons gathered around the table games on the floor of the El Cortez Hotel and Casino were downing drinks, deciding whether to hit or stay, when at exactly 1:25 a.m. the ground shook violently beneath their feet. A second later the gaming floor of the El Cortez plunged into darkness. A few moments passed before the lights flickered back to life, the guests and dealers on the casino floor exchanging confused looks.

As curious patrons filtered out of the El Cortez onto Fremont Street, they encountered a scene that would have been more expected thousands of miles away in the cities of South Vietnam rather than in the center of what by the late-60’s was the undisputed gambling capital of the United States.

Shards of glass littered the street outside the El Cortez as the explosion had shattered windows for several blocks. A plume of grayish-black smoke was rising from the site of the Orbit Inn Motel, one of the two and three-story motels lining the east side of Fremont Street. An enormous gash had been torn into the façade of the building, and soon people began walking in a stunned daze from the rubble of the shattered Orbit Inn.

The explosion at the Orbit Inn would turn out to be the deadliest bombing in the history of Las Vegas. Surprisingly, in a city famous for mafia-linked bombings, this murderous act was carried out by a deserter from the U.S. Army for reasons that are still shrouded in mystery.

The force of the blast ripped through flesh and bone, scattering remains into the streets and alleyways surrounding the Orbit Inn. First responders worked through the night performing the gruesome task of collecting remains of the victims into black body bags arranged on the sidewalk. Police ultimately recovered six bodies from the wreckage of the motel, with a dozen more people treated for injuries.

It did not take long for investigators to determine that the blast originated in Room 214, which was registered to a Richard J. Paris and his wife, Christine. And due to the nature of the damage caused by the explosion, the police were able to determine the blast at the Orbit Inn was caused by a perpetrator employing high explosives.

Richard James Paris was born in Illinois in 1938 to young parents. Paris enlisted in the military at age seventeen and accounts indicate he enjoyed his time in the service. But at some point, Paris’s behavior caused him to be written up for violations of the Army’s code of conduct.

The anger and embarrassment over this official reprimand caused Paris to go AWOL for the first time. He was on the lam for a period of months before deciding he wanted to return to the only career he had ever known. Paris threw himself on the mercy of the military, writing to several generals with a plea to be reinstated to his former position. Paris was convincing, and upon his reinstatement with the Army he was assigned a position as a shipping clerk at Fort Ord in California.

While stationed at Ford Ord, Paris met Christine Swiggum, a woman about five years his junior that had emigrated to the United States with her family from Australia when she was a child. Paris and Christine were eventually wed, and the marriage at least gave the outward appearance of being a happy one.

Things went fine for a period of time until Paris again ran into trouble with his superiors in the Army. It is unknown what he was disciplined for, but in November of 1966, Richard Paris again failed to show up for duty and went AWOL. He and Christine saw his parents one last time that November and on that occasion neither Christine or Richard gave any indication of distress.

The couple settled briefly in Hollywood, California and then seem to have traveled around the country over the next two months. Shortly before landing in Las Vegas in early 1967, Richard Paris made a trip to Phoenix, Arizona where he legally purchased several pounds of dynamite and obtained a permit to transport the explosives.

Shortly after Christine returned to Room 214 a little before 1:30 a.m., a thunderous blast ripped through the Orbit Inn. The theories behind why 28-year-old Richard Paris detonated over twenty pounds of dynamite in downtown Vegas began before all of the victims had even been identified. Some investigators postulated the bombing was the result of a lover’s quarrel, and the Clark County District Attorney openly admitted he just wanted to put out any theory that wasn’t mob-related to limit negative publicity for the city.

The evidence gathered from the bombing scene was eventually forwarded to the FBI to draw a conclusion on the cause of the blast, with the federal agency having a greater ability to synthesize Richard Paris’s movements around the country with evidence recovered at the blast site. FBI investigators returned a verdict that Paris intentionally detonated the dynamite he purchased in Arizona because the AWOL soldier was “bent on suicide because of his troubles in the service.”

Regardless of the motives behind the bombing, Richard and Christine Paris lie side by side today at the Rose Hills Memorial Park in Los Angeles with matching inscriptions on their tombstones: “Our Sunshine and Happiness”

The shattered remains of the vehicle of prominent Las Vegas attorney Bill Coulthard. The slain lawyer had been active in Las Vegas civic life after serving as the first FBI agent at the Las Vegas field office. Hotel owner Benny Binion was suspected of involvement in the blast, though no charges were ever brought against Binion.

the fbi agent and the gangster

Former FBI agent, ex-president of the State Bar of Nevada, two-term member of the Nevada Assembly, and prominent local Las Vegas attorney Bill Coulthard left his law office located in a ten-story downtown office building on the scorching 115-degree summer afternoon of July 25, 1972, and made his way to the parking garage located on the third floor of the building. The attorney entered his vehicle and cracked the windows before inserting his key in the ignition.

An explosion thundered throughout downtown Vegas. Four sticks of dynamite hidden near the steering column of Coulthard’s car detonated with the turn of his key, transforming the vehicle into a twisting hulk of scorched metal and setting several other nearby vehicles alight.

Casino magnate Benny Binion – who was suspected of murdering the wife of a rival back in Dallas with a car bomb – listened to the explosion from his office in the downtown Horseshoe Casino a mere two blocks away from the bomb site. He knew that all of his hard work in Las Vegas wouldn’t be for naught and that his legacy would be protected.

Benny Binion moved to Vegas in 1946 with two suitcases loaded with cash earned from the decades he operated illegal gambling rackets throughout Dallas. Over the years, Benny Binion built a national reputation founded upon his downtown Las Vegas Horseshoe Casino. But Binion didn’t own the land upon which he had built his empire – he leased it. And his principal landlord was none other than Bill Coulthard, who controlled a 37.5% interest in the land Binion’s Horseshoe Casino was situated upon.

Binion’s lease was set to expire in the early 1970’s. And the straight-laced former FBI agent Coulthard was not in the mood to renew the lease of a vicious gangster that had already developed a reputation around Las Vegas for using violence to settle disputes. Benny engaged in furious negotiations in an effort to get Coulthard to come around. But as one of Binion’s associates would later say of Old Man Binion’s efforts to renew the lease, “He tried to negotiate with the asshole, but the son of a bitch wouldn’t budge.”

In the end Coulthard decided to lease the land to new tenants, ones with less questionable backgrounds than Benny Binion’s. But Binion was not about to let the multi-million dollar enterprise he had built from scratch go without a fight.

When Benny Binion needed a dirty job done, he had one man that he knew he could turn to. Tom Hanley was the man Benny Binion relied upon to solve problems via less-than-legal methods. And since the mid-60’s, Tom Hanley had worked with his son, Gramby Hanley, to carry out at least six murders, as well as over a dozen bombings, arsons, and several burglaries throughout Las Vegas.

Sometime in early 1972, Benny Binion determined there was only one way to save the Horseshoe Casino. He paid Tom Hanley a hefty sum to eliminate a problem for him. Tom and Gramby then went to work scouting out Coulthard’s routine, and they were fortunate that Coulthard was a creature of habit, coming and going at usual times from his downtown office.

The daylight execution of Bill Coulthard rocked Las Vegas. The power brokers of the city knew and liked Bill Coulthard, and they demanded action in response to the brutal slaying. The ability to solve the crime would prove that law and order still existed in a town that had made a habit of turning a blind eye to the activities of its less-savory characters.

Beechers Avants, the homicide detective working the case, diligently tracked down leads and within a few months determined that the most likely suspect had been Tom Hanley and that the most likely motive was Binion’s desire to maintain control of his casino. But Detective Avants ran into an insurmountable roadblock – his boss, Clark County Sheriff Ralph Lamb – was a close personal and business associate of Benny Binion. In fact, Sheriff Lamb would face a federal investigation years later in relation to tens of thousands of dollars in “loans” Binion had given the county’s top cop.

Benny was questioned by police in relation to the bombing but denied any responsibility, and the case ultimately went cold. As for Binion’s Horseshoe Club, after Coulthard’s death, the control of his shares fell to his deceased wife’s brothers, who signed a 100-year lease with Benny Binion.

The Las Vegas press covered in detail the attempted assassination of former mob associate, professional gambler, and casino executive Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

an attempt on an old mobster

Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, reputed front-man for organized crime outfits that ran the Stardust Casino for a period, entered his Oldsmobile on the night of October 4, 1982, in the parking lot of Tony Roma’s on East Sahara Avenue. A moment after he turned his key in the ignition, an explosion tore through the rear of Rosenthal’s car.

High explosives placed on the undercarriage of the 53-year-old former gambler and casino executive’s car had been triggered by the turn of the key. But while Rosenthal’s would-be assassins knew his routine well enough to successfully plant the bomb, they were apparently ignorant of the fact that Rosenthal’s Cadillac had a steel floor plate. While the blast was deflected from the driver’s seat, it did tear through the gas tank. Rosenthal opened the driver side door and leapt out only seconds before the fire ignited by the bomb reached the ruptured gas tank, engulfing the vehicle in flames.

Rosenthal suffered burns to his legs and face from the blast – he was transported to Sunrise Hospital and released after a few hours. Two U.S. Secret Service agents in the parking lot were also injured by flying glass. The two agents were part of an advance team scouting areas in preparation for a fundraising visit by the President.

Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department intelligence unit detectives and agents from the local FBI field office immediately directed their suspicion on organized crime figures linked to Chicago, including ruthless mobster Tony “The Ant” Spilotro. Law enforcement saw the murder attempt as an opportunity to recruit a valuable informant to bring down one of the largest organized crime outfits in the country. The head of Metro’s intelligence unit even threatened to withdraw police protection from Rosenthal and his young children if he refused to cooperate, forcing Clark County Sheriff John McCarthy to issue a public apology to Rosenthal.

Rosenthal, eager to avoid any further attempts on his life, issued a statement at a public press conference intended to reach his former associates. “Thanks but no thanks,” Lefty said of police efforts to turn him. “That’s not my style.”

Lefty Rosenthal suffered no further attempts on his life, and by all accounts, he achieved what few mobsters manage – he kept most of his ill-gotten gains and lived to a long age as a free man.

Las Vegas was rocked by a series of bomb attacks against local restaurants. These bombings were the result of a labor war that was detailed by the local press. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

Restaurant Wars

The Culinary Union local in Las Vegas developed into a powerhouse under the leadership of union organizer Al Bramlet. But despite its power, the Culinary Union was unable to bring several off-Strip restaurants into its fold despite decades of picketing.

When conventional organizing methods proved unsuccessful, Bramlet resorted to less savory avenues. On the night of December 20, 1975, as over 300 patrons and 70 staff occupied the high-end Alpine Village Inn restaurant, two bombs tore through the roof of the building near the kitchen. Despite the bombs causing a fire to break out, everyone inside the restaurant was able to make an orderly exit without injury. The lack of loss of life was miraculous – investigators determined that one of the two bombs had nearly ruptured a gas line, which would have instantly reduced the entire building to rubble.

Las Vegas did not have long to recover. The next month, another explosion thundered through the pre-dawn air about a mile west of downtown Vegas on January 12, 1976. The target of this blast was David’s Place, a gourmet restaurant that had long resisted efforts at unionization. Several people at a residential facility for the elderly next door to David’s Place were injured by flying glass. Police investigators determined that the blast had been caused by high explosives left at the rear of the gutted restaurant.

Things remained quiet for the next year. Then, on the night of January 24, 1977, the culprits behind the previous bombings engaged in a dangerous escalation. Security guards at two off-Strip non-union restaurants – the Village Pub and the Seaboard Tack – noticed pools of gasoline beneath jeeps parked near the establishments. Emergency dispatchers received calls from the restaurants a few minutes apart. The local bomb squad determined that each jeep contained 350 pounds of gasoline rigged to explode upon someone opening the car door.

The only injury caused by the improvised explosive devices was to fire marshal Tom Huddleston, who suffered burns when an ignition device he was removing from a jeep went off in his hands and set his shirt alight.

Tom and Gramby Hanley, a father-son hitman team whose handiwork by this point had already left a bloody trail across Las Vegas, had been hired by Bramlet to place the bombs at non-union restaurants. The relationship between the Hanleys and Bramlet had run along smoothly until the failed twin bombings at the Village Pub and Seaboard Tack. Things broke down when Bramlet refused to pay the hitmen $10,000 he promised for the job.

The Hanleys were not one to be stiffed on money they felt was owed. But while the Hanleys wanted to settle their score with Bramlet, they also wanted to avoid unnecessary risks to their safety. It was widely known that Bramlet always carried a .357 revolver on his person in case one of his many enemies tried to do him harm.

In February of 1977, the Hanleys met Bramlet as he exited a plane in Las Vegas after returning from a trip to Reno. The hitmen knew that Bramlet would be unarmed departing his flight. They escorted the union boss from the terminal to the McCarran Airport parking garage and forced Bramlet into a waiting vehicle. Then they drove out to the desert.

A hiking couple discovered Bramlet’s body buried under a pile of rocks dozens of miles outside of Las Vegas a few weeks later. Police determined that the union boss had been killed by a gunshot to the head. But Bramlet’s killers had not left much in the way of clues and the elements had already limited the amount of evidence to be gained from Bramlet’s corpse. The police were at a dead-end as far as suspects in the murder until they received an unlikely break. One of the four men that accompanied Bramlet on his fateful ride out to the desert came forward to reveal the identities of his cohorts.

Though the Hanleys skipped town after murdering Bramlet, they were eventually arrested for the killing. The Hanleys ended up cutting a deal with federal prosecutors that had been investigating the leadership of the Local 226, including their role in the restaurant bombings of 1975 – 1977. In exchange for the Hanleys pleading guilty to the Bramlet murder, prosecutors agreed to allow the Hanleys to serve their life sentences for the crime at a federal prison in San Diego rather than Nevada State Prison in Carson City, where the hitmen feared for their lives.

Al Bramlet grew the Culinary Union in Las Vegas from 1,500 members in 1953 to 24,000 members at the time of his murder. Today, Local 226 has long since moved past the corrupt days of Bramlet to become one of the most powerful and effective unions in the country.