losing your shirt in early vegas

“The orderly, law abiding saloon men are at least deserving of a square deal.”

Block 16, the Red Light District of early Las Vegas, consisted of a row of dive bars and saloons. Travelers through early Vegas entered Block 16 at their own risk. (UNLV Digital Collection)

the allure of the red light district

A sizeable number of the 80,000 or so residents of Nevada in the first part of the 1900’s were prospectors seeking their fortunes in the mining boomtowns that sprung up overnight across the State – places like Goldfield, Midas, and Rhyolite. The chance to become instantly wealthy offered by these isolated locales attracted thousands of single men from across the country, with most passing through tiny rail junction towns like Las Vegas on their way to make a fortune.

One such traveler was George Wood, who stepped off a train at Union Pacific Depot in downtown Las Vegas in the freezing dawn on January 13, 1915. Union Pacific Depot was the economic heart of early Las Vegas and would remain so until the city received its next financial jolt when construction of the Boulder Dam began a few dozen miles to the south.

Wood planned to catch the 10:00 a.m. train to Goldfield later that day. However, Wood was the sort restless enough to pack up with his life’s savings and head to a remote outpost of the Nevada desert to prospect for gold, so waiting around Union Pacific Depot for a few hours wasn’t particularly appealing, especially after Wood caught wind from locals about the town’s Red Light District – Block 16.

Union Station Depot in Las Vegas around the time George Wood made his ill-fated trip to Block 16. (UNLV Digital Collection)

prostitutes and dope fiends

Not long after Las Vegas was founded, the town leaders determined that since it would be impossible to eliminate vice, such activities should be confined to a particular part of the community. The result of this policy decision was the creation of Block 16 and 15 at the intersection of First Street and Wilson Street, the only two areas of town licensed to sell liquor. The bars and saloons in the Red Light District varied in quality and class, with the Arizona Club standing out as the biggest and best-run, but virtually all of the establishments hosted rooms in the back rented by the hour where local sex workers could ply their trade.

It was not a long walk from the train station before Wood arrived at the row of bars and saloons lining the dirt road along First Street. Once Wood made his way to Block 16, he ultimately wandered into one of the less reputable establishments in an already seedy part of town. There he made the acquaintance of Camille Smith, a well-known local prostitute that worked out of the back rooms of Block 16. Camille made such an impression that Wood decided to delay catching his 10 o’clock train in favor of sharing some drinks with his new momentary companion.

At some point, Camille interrupted her conversation with Wood and beckoned over a friend, 21-year-old neer-do-well Glen Harwood, who the local papers described as a “dope fiend” and was known around Vegas for wiling away his time at the saloons before stumbling back to his family’s home on the edge of town. The three new friends drank heavily over the next few hours on Wood’s dime. When their glasses ran dry, Harwood offered to make the trip to the bar to grab the next round, asking Wood for money to purchase the drinks. Not wanting to interrupt his conversation with Camille, Wood kept freely handing Harwood money for drinks and, because of his inebriated state, he didn’t ask Harwood why there was never any change.

As night fell, Wood and Camille decided to take up in one of the rooms at the back of the bar while Harwood went on his way. But Harwood did not go too far. Either Harwood or Camille had slipped “knockout drops” (as the local paper referred to the drug) into Wood’s drinks.

Wood remembered heading toward one of the back rooms of the saloon with Camille – the next thing he recalled was coming to the following morning on one of the cold dirt roads lining Block 16, stumbling about shirtless in the freezing winter air. A sheriff’s deputy found the dazed Wood and ushered him a few blocks to the reputable part of town where the unfortunate traveler was put up in a room at the Overland Hotel until he regained his senses.

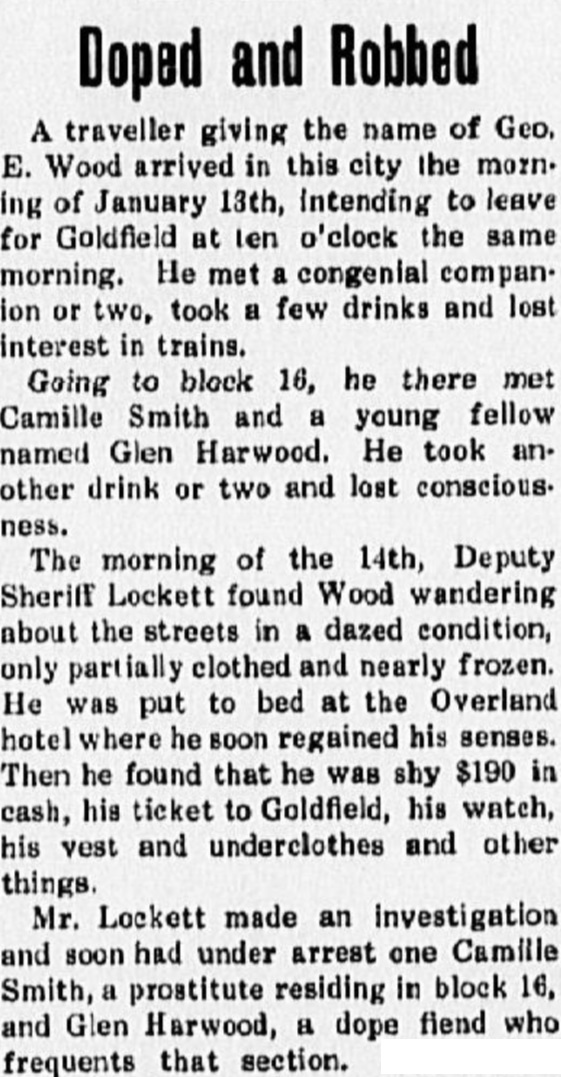

Las Vegas Age newspaper article regarding the Wood robbery. (Las Vegas-Clark County Library District)

drugged, shirtless, and penniless in old vegas

Once Wood came to, he discovered Harwood and Camille had robbed him of $190 (about $4,000 today), as well as a watch, the ticket to Goldfield, and even most of his clothing. Harwood and Camille were quickly identified by Wood as the culprits and arrested. Unfortunately for Wood, police were only able to recover $40 of the stolen money, with the criminal duo likely secreting or spending the majority of the funds.

The robbery of Wood was apparently part of a recent uptick in such crimes around the new town. The local paper reported, “The doping and robbing of drunks is again becoming a leading industry in this city.” Such incidents were common in the early years of Las Vegas after its founding in 1905 but had lessened starting around 1913. But in the two months prior to the Wood robbery, there were multiple other cases of out-of-towners winding up drugged and robbed after visiting Block 16 establishments, with the number of such incidents believed to be higher than the official count as the victims were disinclined to report the circumstances leading up to the thefts.

Harwood admitted his guilt right away under questioning from a deputy sheriff while Camille denied any sort of impropriety on her part. The District Attorney felt Camille was in on the robbery but that he would have a tough time convincing a jury of her guilt. This resulted in the dismissal of charges against the young woman, leaving Harwood on the hook for the crime. Harwood spent a few weeks in the local jail before entering into a plea agreement with the prosecution. He would plead guilty to a lesser charge and serve 30 additional days in the county jail.

The Clark County Jail where local Vegas resident Glen Harwood served out his sentence, but not before he was caught up in an escape plot by two other inmates - Arthur Wells and James Steele, bandits facing charges for a series of robberies. (UNLV Digital Collection)

from “dope fiend” to unlikely hero

Harwood ran into unexpected trouble a few days into his sentence. The deputy sheriff in charge of the jail had a habit of taking non-violent offenders to local restaurants for lunch, which on April 8, 1915 included Harwood and two other inmates incarcerated on petty crimes. Deputy Sheriff Roy Lockett left two inmates behind – Arthur Wells and James Steele, bandits that had recently been hunted down by Undersheriff Joe Keate after conducting a series of armed robberies of stores in the small mining towns of Clark County – while the deputy and other inmates walked a few blocks to a local diner.

Deputy Lockett returned to the jail with his charges after their meal and opened the cell door to let Harwood and the other inmates back to their quarters. The deputy delivered food from the diner to Steele and Wells, then turned around to shut the cell door. But just as the cell door was about to slam shut, Steele approached and complained about the fare from the diner, offering the deputy a coin to buy him some oranges. When Lockett reached for the coin, Steele lunged against the cell door, throwing the deputy off-balance. Wells then ran out of the cell and broke a heavy oak leg off of a nearby table, using the leg as a club to repeatedly bash Deputy Lockett’s head.

Harwood, having cleaned out from his opium habit during his months in the county jail, showed his true character by entering the fray in an effort to defend Deputy Lockett, but Wells turned his attention to Harwood and struck him several times with the table leg. The attack was over in seconds. Steele and Wells fled the prison as fast as their feet could carry them and rushed out of town. A posse of local townsfolk and sheriff’s deputies numbering close to a dozen soon followed, venturing out on horseback and by automobile to search the mesquite brush in the dunes surrounding Las Vegas.

The desert surrounding early Las Vegas was thick with mesquite brush, offering plenty of opportunities for escaped prisoners Wells and Steele to conceal themselves while fleeing a sheriff’s posse. (UNLV Digital Collection)

a surprise verdict for the escape artists

The posse caught up with the inmates within a few hours of their escape while the pair were hiding in a clutch of mesquite brush. Wells surrendered without incident, but Steele managed to evade his pursuers by darting deeper into the mesquite and using the overgrowth for cover until darkness fell. The escaped inmate then slipped past a cordon set up by the posse until he arrived at a ranch and stole a horse to make a more expeditious getaway.

Members of the sheriff’s posse on horseback spotted Steele the following morning and trailed him until he stopped to rest near the Colorado River. Posse members demanded Steele’s surrender. But the fugitive had different plans than returning to jail, so he bolted toward a nearby canyon. The posse opened fire and Steele stumbled, struck by one of the rounds, but this did not stop him from making his way to the canyon. The posse attempted to locate Steele but he managed to conceal himself amidst the winding ravines and mesquite along the canyon floor.

Steele eventually made his way over the Colorado River and into northern Arizona, which transformed the escape from the Clark County jail into an interjurisdictional manhunt. The posse from Vegas, rested and with fresh horses, regrouped and joined forces with Arizona sheriff’s deputies to renew the hunt for Steele. Four days after the brazen jail break, the posse caught up with Steele near an isolated mesa in Mojave County. Facing drawn guns, Steele surrendered, quipping, “I suppose I will get life for this.”

Steele and Wells stood trial for the assault on Deputy Lockett and Harwood, as well as for the escape, in a Las Vegas courtroom in the fall of 1915. The attorney for the defendants did not dispute the facts surrounding the jail break, but he did put forward the novel argument that his clients had been unlawfully detained, and therefore they were justified in using force to break out of jail.

The law requires suspects to be brought before a judge “without unreasonable delay” upon being arrested. It turned out that Steele and Wells had been languishing in the cramped quarters of the Clark County Jail for 23 days after their arrest without being arraigned before a judge. The jury agreed that this constituted an unreasonable delay and found the pair “not guilty.” However, the high from this victory was short-lived for the bandits, as both were convicted of multiple robberies in subsequent trials, with each receiving a 5 – 20 year sentence in the Nevada State Prison.

1920 Census for Las Vegas showing Glen Harwood’s more stable lifestyle (Line 33).

harwood turns his life around

Harwood recovered quickly from the injuries he sustained in the jail break and served out the rest of his sentence in the county jail without incident. Harwood apparently turned his life around after the events of 1915. By 1920, Harwood was living with his sister, brother-in-law, and niece in Las Vegas making an honest living as an auto mechanic.

As for the unfortunate would-be prospector George Wood, it is unknown if he ever made it to Goldfield. And Camille Smith only appears in this one local press article before fading back into the history of early Las Vegas, well known only to those living in that same small place and time.