child abduction and Swift Justice in old west Vegas

“You’ve got one hour to get out of town, but you’ve got two minutes to get out of my sight.”

Las Vegas Age headline from January 9, 1909, recounting both the attempted abduction of a child in the newly founded town of Las Vegas and the swift justice administered in the last days of the Old West. (UNLV Digital Collection)

stranger danger - then and now

Those of us that grew up in the 1980’s and early-90’s remember the ever-present (often media hyped) threat of “Stranger Danger.” Las Vegas was no different, and these authors remember as young children attending events hosted by the local police department where we were greeted by McGruff the Crime Dog and had our fingerprints taken despite the threat of child abduction being about one in a million. But sensationalism does not mean the threat of child abduction is nonexistent.

A story from 1909, shortly after the founding of Las Vegas, offers a glimpse into the similarities in reactions to cases of child abduction then and now, as well as how swift “justice” was often carried out in frontier towns like Las Vegas in the last days of the “Old West.”

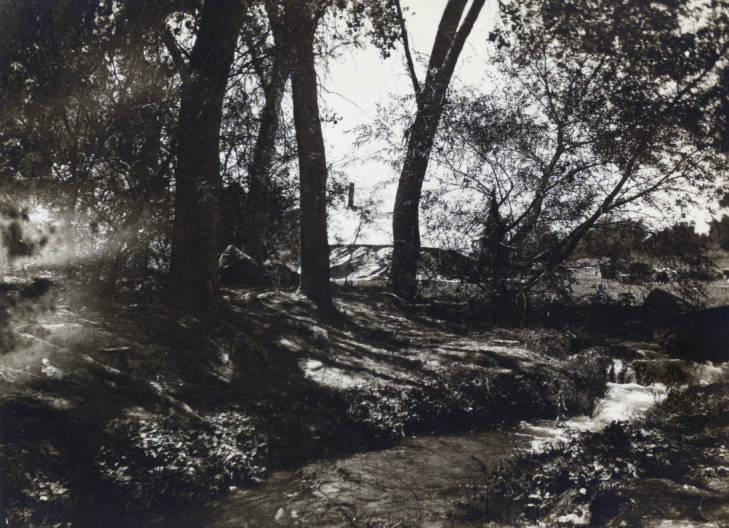

The old Las Vegas Creek at the time the Romero child went missing. Today this area is around the intersection of Washington Avenue and Las Vegas Boulevard. (UNLV Digital Collections)

A girl doesn’t return home from school

It was frigid on the morning of Monday, January 4, 1909 in the young town of Las Vegas. A five-year-old girl exited the small cottage-style Romero household located in “Old Town” - the less-developed original townsite for Las Vegas that was largely vacated shortly after the city’s founding in 1905 – and made her way along the dirt roads to the town’s small one-building schoolhouse.

Sometime in the early afternoon, Mrs. Romero grew increasingly distracted from her household responsibilities when her child failed to return home from school on time. She knew something was wrong within minutes of her child failing to return home by the regularly scheduled time, prompting Mrs. Romero to walk out into the dirt streets, hoping her fears would be eased by the sight of her daughter strolling down the street with a reason for her delay. But there was no sign of her little girl.

Now frantic, Mrs. Romero caught the attention of her neighbors, asking if any had seen her daughter. As Mrs. Romero made her way closer to the schoolhouse street-by-street, someone mentioned they had seen her child walking with a man near the Las Vegas Creek on the edge of town.

The bakery where Walter Smith worked at the time of the attempted abduction of the Romero child. (UNLV Digital Collection)

A Suspect nabbed in Time

Within a few minutes Undersheriff Sam Gay and his deputy, along with concerned townspeople and Mrs. Romero, fanned out near Las Vegas Creek, a narrow stream shaded by trees and dotted with the occasional shack snaking along the eastern edge of town. The Las Vegas Creek had provided a source of water to the Las Vegas area since the first permanent American settlement in the area - the Old Mormon Fort. Mrs. Romero yelled her child’s name as she walked accompanied by a sheriff’s deputy.

Just as darkness began to fall on the short winter day, the Romero child called back to her mother, “I’m over here.” Mrs. Romero and the sheriff’s deputy ran toward the child’s voice, but by the time they reached her the man that had lured her to the overgrown banks of the creek managed to dart into the growing shadows.

Las Vegas in 1909 only had a population of 800 people, so it did not take long before questioning of witnesses by Undersheriff Gay and his deputy led to the arrest of a newcomer to the city – one Walter Smith, who had arrived from California a week earlier and taken up a job at the Las Vegas Bakery in Old Town. There is virtually no information that could be found about Smith and he likely was among the frequent transient travelers that hopped the rails searching throughout the west for work during the early years of the 20th century.

And like most abduction cases today, Smith was not a complete stranger to the Romero child. The bakery he worked at was in the same neighborhood as the Romero household, and Smith had likely seen the Romero child before the day of the attempted abduction, perhaps even making preliminary approaches to the child with small talk.

The Las Vegas courthouse where suspect Walter Smith was brought before Judge Lillis to face questioning over the attempted abduction of the Romero child. (Las Vegas Historical Society)

frontier justice

While the city had a jail with notoriously harsh conditions, Undersheriff Gay saw no reason to delay the administration of justice. Local Judge Henry Lillis was summoned to the squat one-story courthouse to question the detained suspect. Smith protested his innocence despite witnesses placing him walking with the Romero child along the creek. Plus, Smith lacked a solid alibi for his whereabouts during the time the Romero girl went missing after school.

Judge Lillis found there was significant circumstantial evidence to back abduction charges against Smith and that the recent arrival to town had likely intended to harm the Romero child. But there was still not enough evidence by which a jury could convict the suspect.

Normally, a suspect is free to go about their business when a court finds there is insufficient evidence to prosecute. But such matters worked a bit differently in towns on the frontier during the waning days of the Old West.

Judge Lillis ordered Walter Smith to leave Las Vegas within the next hour. Undersheriff Sam Gay then turned to the suspect and told him he had just two minutes to get out of Gay’s sight. News accounts indicate this was one minute and forty-five seconds longer than needed for Smith.

Undersheriff Sam Gay, top, and Las Vegas Justice of the Peace Henry Lillis, who oversaw the swift justice administered against Walter Smith on suspicion of child abduction (UNLV Digital Collection)

the practical limits of due process

Such orders were not uncommon on the frontier and were largely dictated by the circumstances of such isolated locales. For instance, the Vegas city jail was small and intended only to house suspects for a short period of time pending trial, and folks that were convicted were then sent by rail to the Nevada State Prison more than three hundred miles away in Carson City. And there was no effective means of monitoring a man that was determined to pose a threat to the community while out on bail.

Another factor weighing on judges like Henry Lillis in issuing orders that essentially amounted to exile was the lack of recourse for suspects like Walter Smith. First, in 1909 many of the criminal rights we have today did not apply in State court proceedings – a legal process called “incorporation” has made binding on State courts rights such as the protection against unreasonable search and seizure, to remain silent, or to have an attorney. But in the early years of the 20th century, virtually none of the rights outlined in the Bill of Rights were binding on State courts – which makes it questionable as to whether such exile orders would have even been viewed as unconstitutional by a federal appellate court of the time.

Next, as a more practical matter, when the local judiciary and law enforcement tell a suspect to get out of town, there is considerable risk of bodily harm that would accompany any criminal suspect that tried to fight such an order. And a newcomer to Vegas like Smith would have been taking a considerable risk to his personal safety by challenging the order knowing that in the interim he was essentially barred from seeking the assistance of local government or law enforcement for protection against violence.

Public Service Announcement regarding “Stranger Danger” featuring McGruff the Crime Dog, circa 1980’s. While the adorable mascot helped promote public awareness of a few high-profile cases of random child abduction, in large part the public relations campaign obscured the rare nature of child abduction.

media hysteria - then and now

Our story began with the “Stranger Danger” hysteria of the 1980’s and early 90’s. It is telling that the local news account of the attempted abduction of the Romero child concluded by chiding the mothers of Las Vegas to “keep close watch of their children and not permit them to dally on the way to or from school” due to the “fact that the winter travel of the hobo tourists is now at its height.”

A recurring theme in the local press accounts from the early days of Las Vegas, which was a key rail junction, is the city’s frustration with “hobos” and “tramps” that would make a pit-stop in town while hopping the rails, engaging in begging, petty theft, or low-grade grifts. This attempted abduction by a newcomer (albeit one that had obtained gainful employment) was placed in the existing press narrative regarding out-of-control hobo crime.

Las Vegas Age article about the attempted abduction of the Romero child cautioning mothers to mind their children in light of the increased number of “hobos” in the Vegas area. (UNLV Digital Collection).